A late Aptian planktic foraminiferal assemblage and pyrite framboids from the “Otates Horizon”, Cerro Boludo, Hidalgo, Mexico: Paleoecological and paleoenvironmental implications

Lourdes Omaña1,*, Iriliana López-Caballero2, and Fernando Núñez -Useche3

1 Departamento de Paleontología, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510, Mexico City, Mexico.

2 Facultad de Ciencias Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510, Mexico City, Mexico.

3 Departamento de Procesos Litosféricos, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510, Mexico City, Mexico.

ABSTRACT

Cretaceous carbonate deposits are widely distributed along the Sierra Madre Oriental thrust belt from northern Veracruz to southern Nuevo León. At Cerro Boludo (Hidalgo), dark marly limestone samples were collected from the “Otates Horizon”. The samples include a well-preserved planktic foraminiferal assemblage composed of Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and ten Dam, 1948, Globigerinelloides ferreolensis (Moullade, 1961), Globigerinelloides barri (Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957), Globigerinelloides aptiensis Longoria, 1974, Globigerinelloides blowi (Bolli, 1959), Hedbergella roblesae (Obregón de la Parra, 1959), H. occulta Longoria, 1974, H. luterbacheri Longoria, 1974, H. similis Longoria, H. trochoidea Longoria, 1974, H. semielongata Longoria, 1974, Pseudoplanomalina cheniourensis (Sigal, 1952) and Schackoina cenomana Schacko, 1897. Radiolarians are also present. Based on the planktic foraminiferal assemblage we recognized the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone of early late to middle late Aptian age.

The paleonvironmental reconstruction inferred from the lithology and the foraminiferal association suggests an open pelagic deposit, besides the occurrence of pyrite framboids and the organic matter indicate oxygen-depleted conditions in a meso to eutrophic setting probably linked to the “late Aptian anoxic event”.

Key words: foraminifera; late Aptian; “Otates Horizon”; Cerro Boludo; Hidalgo; Mexico.

RESUMEN

Los depósitos carbonatados del Cretácico están ampliamente distribuidos a lo largo del cinturón de pliegues y cabalgaduras de la Sierra Madre Oriental desde el norte de Veracruz hasta el sur de Nuevo León. En la localidad de Cerro Boludo (Hidalgo) se colectaron muestras de margas calcáreas provenientes del “Otates Horizon” que incluye un conjunto de foraminíferos planctónicos bien conservados, compuesto por Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and ten Dam, 1948, Globigerinelloides ferreolensis (Moullade, 1961), Globigerinelloides barri (Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957) Globigerinelloides aptiensis Longoria, 1974, Globigerinelloides blowi (Bolli, 1959), Hedbergella roblesae (Obregón de la Parra, 1959), H. occulta Longoria, 1974, H. luterbacheri Longoria, 1974, H. trochoidea Longoria, 1974, H. similis Longoria, 1974, Pseudoplanomalina cheniourensis (Sigal, 1952) and Schackoina cenomana (Schacko, 1897). Los radiolarios también están presentes.

Con base en el conjunto de foraminíferos planctónicos fue reconocida la Zona de Rango Total Globigerinelloides algerianus de la parte temprana a media del Aptiano tardío. La reconstrucción paleoambiental deducida de la litología y de la asociación de foraminíferos sugiere un depósito pelágico abierto; además la presencia de framboides de pirita y materia orgánica indican condiciones de disminución de oxígeno en condiciones meso a eutróficas vinculadas probablemente al “evento anóxico del Aptiano tardío”.

Palabras clave: foraminíferos; Aptiano tardío; “Horizonte Otates”; Cerro Boludo; Hidalgo; México.

Manuscript received: november 21, 2021

Corrected manuscript received: march 3, 2022

Manuscript accepted: march 4, 2022

INTRODUCTION

The planktic foraminifera are generally abundant and well preserved in mid-Cretaceous marine sediments; they have been affected during the OAEs (Oceanic Anoxic Events) (Leckie et al., 2002; Premoli Silva et al., 1999; Föllmi, 2012; Kuroyanagi et al., 2020).

The greenhouse climate of the mid-Cretaceous was related to ocean crust output that increased considerably, forming an extensive, thick oceanic plateau named the Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs), including the Ontong Java Plateau (OJP) (early Aptian), the Kerguelen Plateau (late Aptian–early Albian), and the Caribbean Plateau (Cenomanian–Santonian) (Tarduno et al., 1991; Leckie, et al., 2002; Bottini et al., 2015; Erba et al., 2015).

The relationship with OAEs suggests that these submarine volcanic events provoked perturbations in ocean chemistry and fertility, providing nutrients (especially iron) that advance to sulfate reduction in the water column, with the precipitation of pyrite framboids, as well as the deposition of organic matter evolving from a poorly oxygenated stage to an anoxic and finally euxinic stage (Jenkyns, 2010).

The pyrite framboidal structure is one of the important characteristics of anoxic conditions (Wignall et al., 2005) that can be preserved through geologic time. Within the water column, the framboids quickly precipitate, presenting a small average size, while early diagenetic framboids in the sediment present larger sizes (Wilkin et al., 1996).

The Aptian is distinguished by climate changes and extreme environmental perturbations, including OAEs, that represent a global phenomenon of organic-matter burial in oxygen-depleted oceans. In addition to the well-known Selli Event in the early Aptian, Sliter (1989a) recognized a level rich in organic carbon from the Franciscan Complex, California. Later (1999 ), this author used the name “Thalmann Event” for a perturbation of the carbon cycle and placed it between the Globigerinelloides ferreolensis and Gl. algerianus zones of late Aptian age.

In Santa Rosa Canyon (Mexico), Bralower et al. (1999, p. 427) recorded a sharp increase in δ13C org values in the planktic foraminiferal Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone (segment C9) followed by level δ13C org values (segment C10) for the upper parts of the same zone.

Leckie et al. (2002, p. 13) indicated that between OAE1a and OAE1b, a black shale event in the late Aptian within the Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone may be another OAE, as was previously cited by Bralower (op cit).

Friedrich et al. (2003) documented several episodes, among them a black-shale horizon, the “Niveau Fallot 4,” within the Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone in the Vocontian Basin of southern France.

Herrle et al. (2004, fig. 5) record marly black shale horizons from the Mazagan Plateau marked by positive carbon isotope excursion, including the Globigerinelloides algerianus.

Yilmaz (2008) documented black shale-mudstone interval of Upper Aptian that has been recorded within the Globigerinelloides algerianus-Pseudoplanomalina cheniourensis zones in the Deirmenözü section at NW Turkish (fig. 3, p. 288).

Hosseini and Conrad (2010) recorded an interval dated as late Aptian (Gargasian), the Globigerinelloides ferreolensis Zone, which correlates with a major ocean anoxic event (OAE). The occurrence of planktic foraminifers with radial chambers; Leupoldina reicheli, L. pustulans and Hedbergella roblesae, was interpreted as an adaptation to a depleted oxygen environment from a section at west of the Kazerun Faul, throughout the Zagros Fold Belt, SW of Iran.

The objective of this study is to report and describe the planktic foraminifers that are used for dating, moreover we analyzed the planktic foraminifera paleoecology, in addition we infer the depositional environment based on the microfacies, the foraminiferal association and framboidal pyrite occurrence.

Geological Setting

During the Early Cretaceous, the Gulf of Mexico basin was tectonically stable except for continuing slow subsidence of its central part, growth faulting of the margins of some depocenters and local deformation related to underlying Jurassic salt. The Lower Cretaceous rocks are carbonates and evaporites on the shelves and carbonates in the bathyal areas (McFarlan and Menes, 1991).

In Mexico, the first Lower Cretaceous investigations of the surface and subsurface were carried out by Heim (1926), followed by Burckhardt (1930), Muir (1936), Imlay (1944), Bodenlos et al. (1956). Since then, there has been a proliferation of litho-stratigraphical terms.

According to Muir (1936) the term Tamaulipas limestone first has been used by Stephenson (1921) in a private study for the Mexican Gulf Oil Company.

Belt (1925) indicated that “the Tamaulipas limestone outcrops typically in the Sierra Tamaulipas and in the first ranges of the Sierra Madre, west of Ciudad Victoria, and is given the name of Tamaulipas on account of its abundant occurrence and typical development in the state of Tamaulipas. It has also been observed in the front ranges of the Sierra Madre from Tamazunchale to a point southeast of Coyutla, Veracruz. The Tamaulipas formation is a fine-grained, compact limestone with well-marked bedding. The uppermost is predominantly gray in color and contains many chert lenses and nodules of irregular shape. The color of the cherts varies from black to almost white. The lower part of the formation consists of creamy to white compact limestone”.

Muir (1936, p. 23) stated that “the Tamaulipas limestone has never been defined in the literature with reference to a definite type locality. It crops out in and forms the main mass of the Sierra de Tamaulipas and is well developed in the Sierra de San Carlos farther north. This facies exists in the front ranges of the Sierra Madre Oriental southeast of Tamazunchale. From Monterrey to Victoria and far south as Gómez Farias it forms the bulk of the front ranges”, but although the name is considered an informal name, it is widely used in the literature. This author shows the subdivision of Tamaulipas limestone in lower and upper divided by the "Otates horizon" as dark rock 20-30 feet thickness, considered as a distinct key horizon markedly different from the white limestone above and below it (p. 38, fig. 8).

According to Longoria (1975, p. 45) the biostratigraphic position of the "Otates limestone member" correspond to Globigerinelloide algerianus Zone of late Aptian age.

Ross and McNulty (1981) indicated that the Tamaulipas limestone is composed of resistant, light gray to black, thin- to thick-bedded wackestone and mudstone in the Sierra de Santa Rosa, Nuevo León. It is about 800 m thick and is delimited at base by the Taraises and the Cuesta del Cura in the top. A medial unit (64 meters) of black, laminated, thin-bedded wackestone permits division of the succession into three parts, for which many different stratigraphic names are applicable. Microfossils are rare to scarce in the lowest unit but are abundant in the medial part and common in the upper unit. The microfauna is pelagic dominated by foraminifers, radiolarians and colomiellids, nannoconids, calcispheres, that are abundant at some levels in the upper unit. Chronostratigraphically useful taxa suggests that all the lower unit of the Tamaulipas is Hauterivian and Barremian. The middle unit is Aptian, and the upper unit is lower Albian.

The Chapulhuacán Limestone was informally defined by Bodenlos et al. (1956, p. 301). This author states that it was previously named “Tenestipa limestone” and described by Heim (1926). It is located NW of Tamazunchale and takes the name of the village Chapulhuacán located on Federal Highway 85, and its lithology may be comparable to the lower Tamaulipas limestone referred to by Muir (1936).

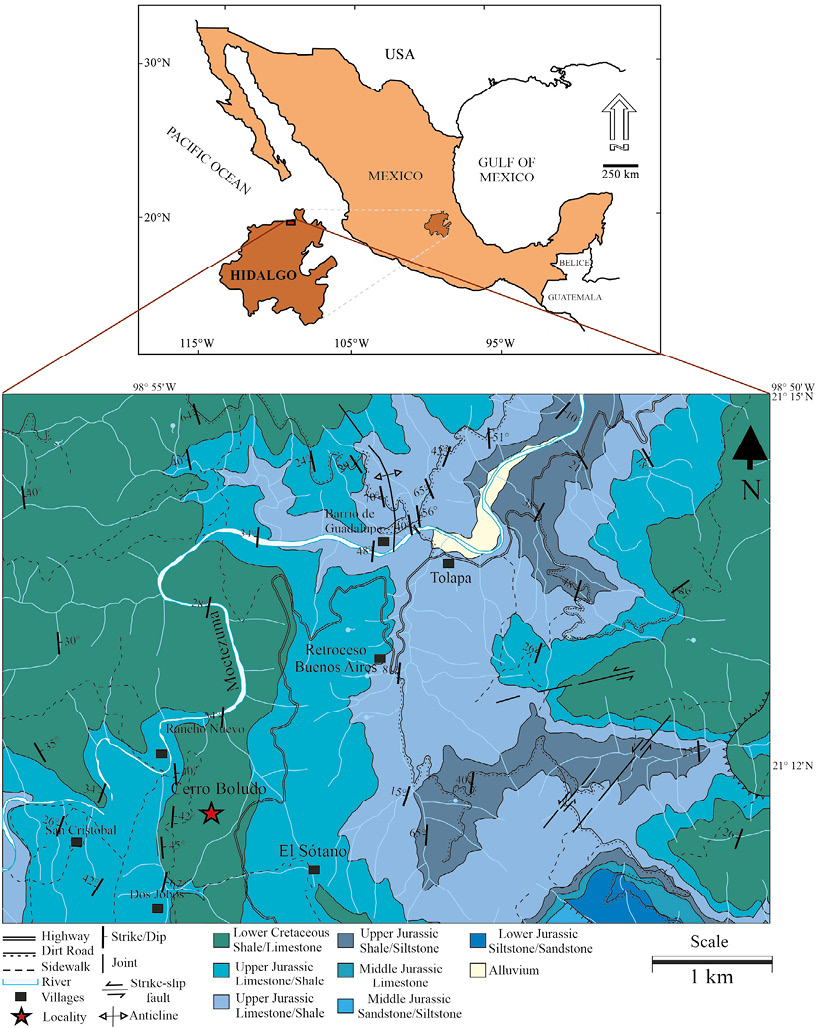

Figure 1. Geological map showing the section studied at the Cerro Boludo site, Hidalgo (Geological-Mining Chart Chapulhuacán F14-D41, scale 1:50000 of the SGM, 2004).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

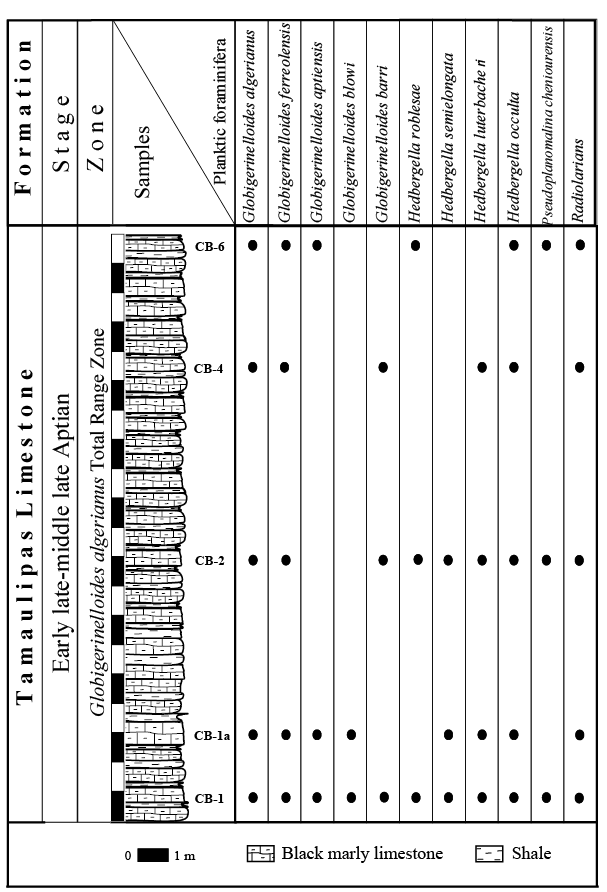

The samples were collected from the Cerro Boludo locality (Figure 1), which is located at the north of the state of Hidalgo, at kilometer 250 of Federal Highway 85 (Mexico–Laredo), between the towns of Chapulhuacán and Tamazunchale. The outcrops are located at 21º 11.742' N and 98º 54.333' W. The section has a reduced thickness of approximately 20 m. consisting of black marly limestone of medium thickness, with intercalations of shale in thin layers (Figure 2).

For micropaleontological and microfacies analysis the samples were prepared in thin sections 50 µm thick, obtaining axial and equatorial sections of the planktic foraminifera. The identification of the species in thin section is based on the papers of Sliter (1989b; 1992) and Premoli Silva and Verga (2004). The age assignment follows the zonation proposed by Premoli Silva and Verga (2004) and Coccioni (2020).

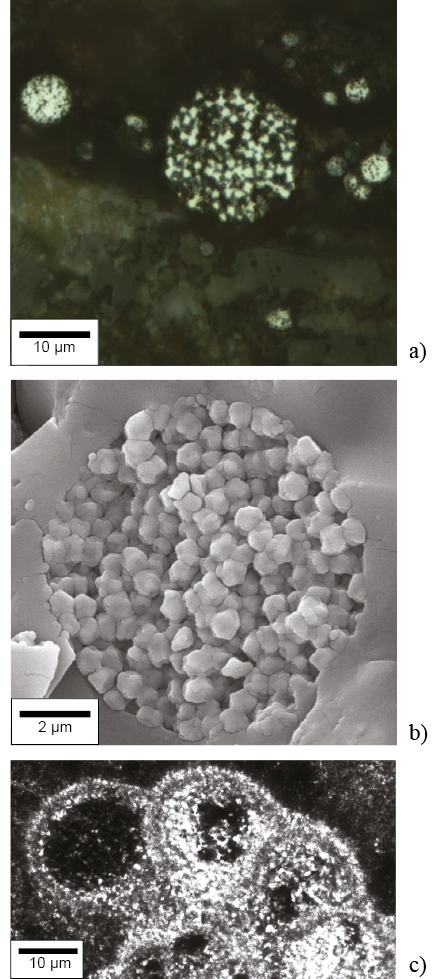

Pyrite framboids were observed in thin sections using a reflected-light Olympus BX-60 microscope at magnifications of 50x and 100x and a low-vacuum Hitachi TM-1000 table-top scanning electron microscope (SEM).

RESULTS

Biostratigraphy

The biostratigraphic significance of planktic foraminifera is widely recognized, as they are a valuable tool in dating, so they permit us to determine the age of the samples studied from the Cerro Boludo locality.

Based on the planktic foraminiferal assemblage we record the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone.

Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone

Author : Moullade, 1966.

Definition: Total range of the nominate taxon.

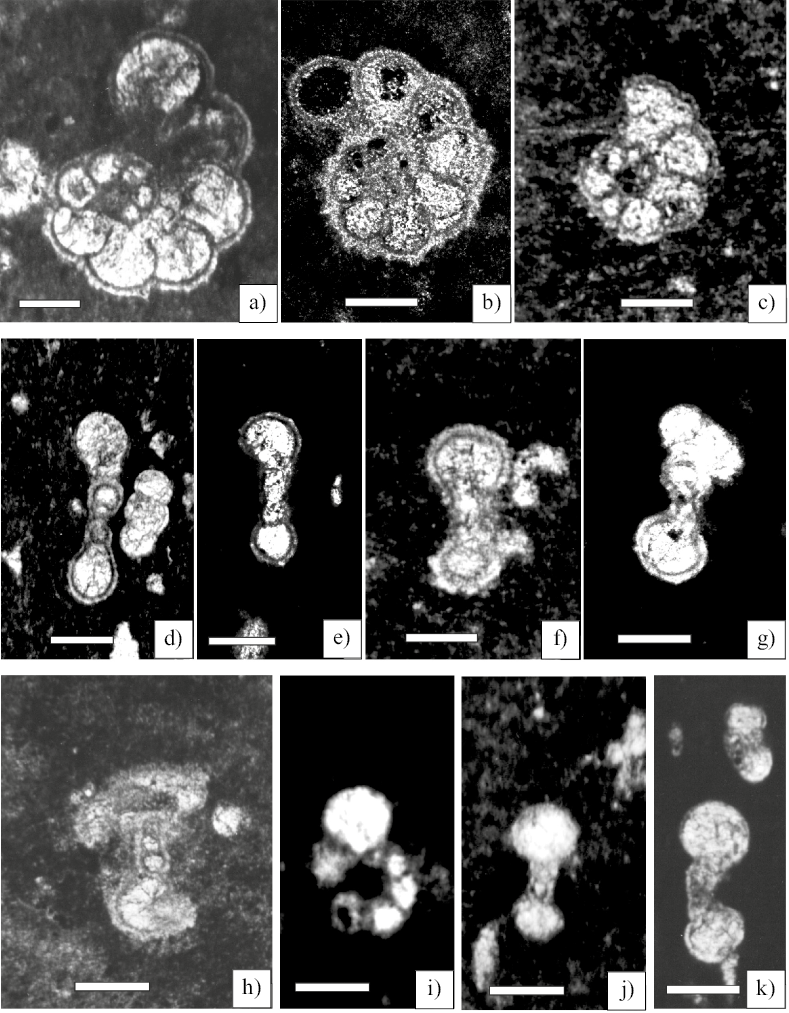

Remarks: This zone is characterized by an assemblage composed of common to abundant large taxa as Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and ten Dam, 1948, G. barri (Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957), moreover G. ferreolensis (Moullade, 1961), G. aptiensis Longoria,1974, G. blowi (Bolli, 1959), Pseudoplanomalina cheniourensis (Sigal, 1952), as well as Hedbergella roblesae (Obregón de la Parra, 1959),

H. occulta Longoria, 1974, H. luterbacheri Longoria, 1974 and H. similis Longoria, 1974 (Figures 3, 4).

Age. According to the zonal schema for tropical regions (Caron, 1985; Premoli Silva and Sliter, 1995; Robaszynski and Caron 1995; Premoli Silva and Verga, 2004), the age assigned to the zone is late Aptian, however recently, Coccioni (2020, p. 288) refined the assignment age and he gave an early late Aptian to middle late Aptian to this interval.

Paleoecology and Paleoenvironment

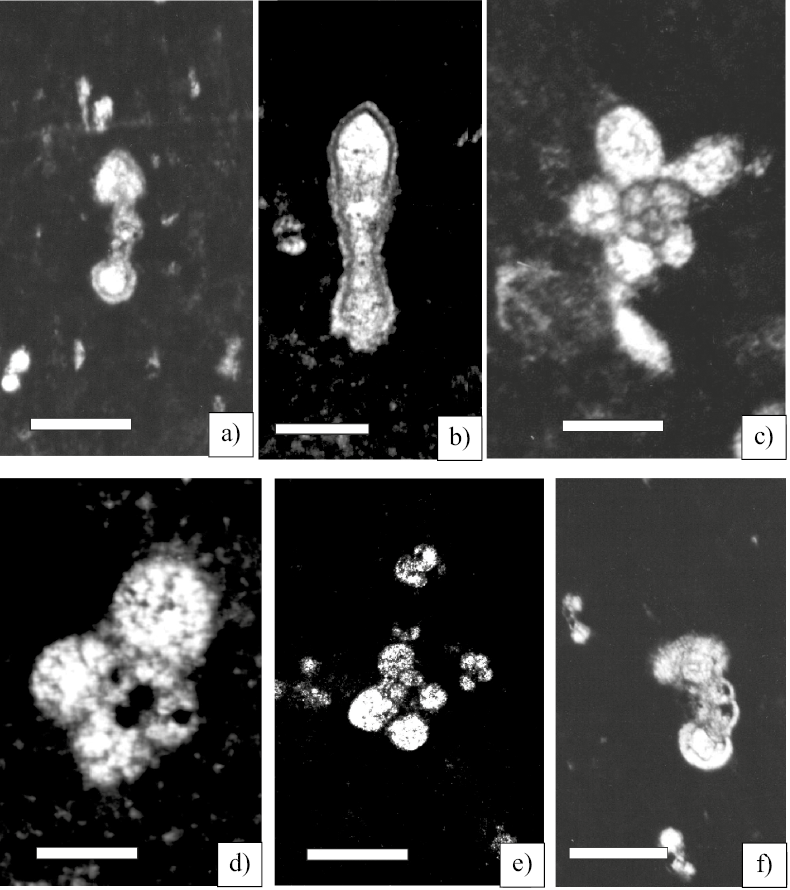

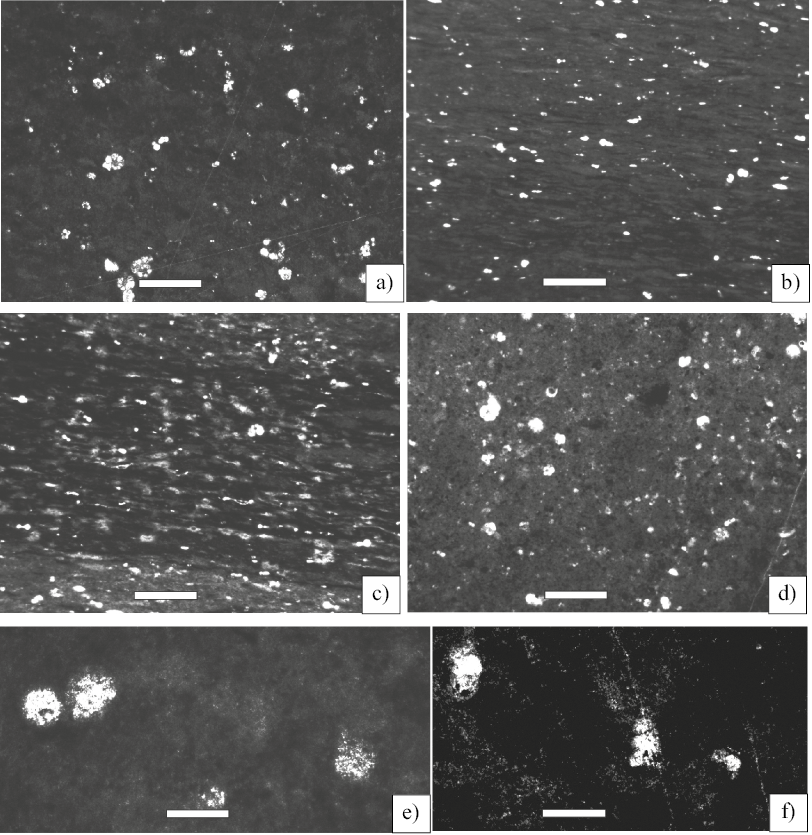

Microfacies 1- Pelagic foraminiferal-radiolarian wackestone (Sample CB-1 and 1a); the components of the microfacies are planktic foraminifers such as globigerinelloids, and hedbergellids with elongated chambers. The radiolarians are common. The foraminiferal chambers are filled with pyrite. Organic matter is uniformly distributed in the micritic matrix and contain framboids (Figure 5a).

Microfacies 2- Planktic Foraminiferal wackestone (Sample CB-2); laminated organic matter is intercalated with the micrite with abundant skeletal grains of planktic foraminifers and radiolarians. Fabric of this microfacies is mud-supported. (Figure 5b).

Microfacies 3- Foraminiferal wackestone-packstone (Sample CB-4); with abundant of planktic foraminifers and radiolarians preserved in micrite. The main characteristic of this microfacies is the gross bed of laminated organic matter containing framboids (Figure 5c)

Microfacies 4- Foraminiferal-radiolarian wackestone (Sample CB-6); this microfacies is defined by a mixed micrite and organic matter and the planktic foraminiferal association with gobigerinelloids, hedbergellids, as well as benthic foraminifera (Figure 5d).

Framboids are the most common form of pyrite in the studied samples. They occur randomly distributed in the micritic matrix and within intra-skeletal pores, as single framboids and clusters of framboids. Individual pyrite framboids are generally < 8 μm (Figure 6a, 6b, 6c).

The distribution of planktic foraminifera is controlled by conditions such their position in the water column, which is likely to be most critical. Test morphologies may function in relation to the density of the foraminifera and its difference from water, as well as resistance to sinking and turbulence. These foraminifera probably utilize different feeding, reproductive, behavioral, and life history strategies in eutrophic and oligotrophic waters (Lipps, 1979).

Other environmental factors, such as temperature, stratification, light intensity, and food availability affect the growth and distribution of the individual planktonic foraminifera (Schiebel et al., 2001; Žaric et al., 2005; Kretschmer et al., 2018).

We documented the depth ecology of some planktic foraminifera observed in the studied interval.

The genus Hedbergella is opportunist or r/strategist with varied depth habitats and an affinity for eutrophic conditions, probably adapted to changes in temperature, salinity, nutrients, and oxygen inhabiting the near-surface waters, likely depending on primary productivity (Premoli Silva and Sliter, 1999). Thus, Aptian hedbergellids may have been able to change habitats in the water column and tolerate wide environmental variations (Hart, 1999; Price and Hart, 2002).

The planktic foraminifera with radially elongate chambers such as Hedbergella roblesae and H. similis indicate an adaptive response to oxygen depletion (Magniez-Jannin, 1998; Premoli Silva and Sliter, 1999; Coccioni et al., 2006).

The Globigerinelloides species are regarded as the most specialized r/k strategists, possibly mesotrophic forms during the Aptian interval (Coccioni, Erba and Premoli Silva, 1992; Premoli Silva and Sliter, 1999).

Based on the textural features characteristics, we identify the Standard Microfacies (SMF 3-For) (Flügel, 2010) corresponding to pelagic deep-water basinal facies (FZ 1) of Wilson (1975). In addition, the foraminiferal assemblage and the microlaminated fine-grained texture with organic matter and framboids of pyrite, indicate a pelagic deep-water oxygen-deficient environment in the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone in the late Aptian. In addition, the presence of radiolarians indicates ocean eutrophication.

Figure 3. Planktic Foraminifera from the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone Scale bar 50 µm. a) Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and ten Dam equatorial section (Sample CB-1). b) axial section (Sample CB-4). c) Globigerinelloides ferreolensis equatorial section (Sample CB-1). d) Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and ten Dam axial section (Sample CB-1). e) Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and ten Dam axial section (Sample CB-4). f) Globigerinelloides ferreolensis (Moullade ) equatorial section (Sample CB-1). g) Globigerinelloides barri (Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957) Axial section (Sample CB-1a). h) Globigerinelloides barri (Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957) Axial section (Sample CB-1). i) Globigerinelloides blowi (Bolli ) Axial section (Sample CB-1). j) Globigerinelloides aptiensis Longoria equatorial section (Sample CB-1). k) Hedbergella luterbacheri Longoria equatorial section (Sample CB-2).

Figure 4. Planktic Foraminifera from the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone. Scale bar 50 µm. a, b) Pseudoplanomalina cheniourensis (Sigal ) axial section (Sample CB-2); b) (Sample CB-6). c) Hedbergella roblesae (Obregón de la Parra) equatorial section (Sample CB-1). d) Hedbergella similis Longoria equatorial section (Sample CB-1). e) Hedbergella semielongata Longoria (Sample CB-1). f) Hedbergella occulta Longoria equatorial section (Sample CB-1).

The name “Tamaulipas limestone” was employed by Stephenson (1921, in Muir 1936) in a private report for the Mexican Gulf Oil Company. Subsequently Belt (1925) stated that the lower limit of this unit was not observed by him, but that the San Felipe beds overly it with a marked lithological change but without evidence of angular disconformity.

Muir (1936) illustrated a tripartite division for the Tamaulipas limestone in lower and upper Tamaulipas. The Otates horizon is in the middle part.

The Tamaulipas limestone is widely distributed, typically in the Sierra de Tamaulipas and the front ranges of the Sierra Madre in northeastern Mexico. It has been studied by several authors, Humphrey and Diaz (1956) , Carrillo Bravo (1961), Enos (1974), Longoria (1975), Gamper (1977), and Chavez Cabello et al. (2011).

Ross and McNulty (1981) studied the microfossils dating the Tamaulipas limestone, from the Hauterivian to Albian in the Santa Rosa Canyon, Sierra Madre Oriental, Nuevo León.

In the study of the Tamaulipas limestone outcropping in the Cerro Boludo locality in northern Hidalgo state, we identified for the first time the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone, based on the stratigraphic distribution of the planktic foraminifera.

Age assignment for this interval is early late Aptian to middle late Aptian according to Coccioni (2020) in the recent zonal scheme proposed for the Tethys Realm.

This zone has been recorded in Mexico; for instance, in the Santa Rosa Canyon, Nuevo León (Longoria, 1975, 1984; Ross and McNulty, 1981; Bralower et al., 1999) and in the Sierra de Parras (Lehmann et al., 1999, p. 1018).

For the paleoenvironmental interpretation, the microfacies analysis and the foraminiferal assemblage for the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone from the “Otates horizon” indicate that the deposit took place in a pelagic deep-water environment in the studied locality.

In this zone, the presence of planktic foraminifera with elongated chambers, adapted to stressed conditions which are frequently found in deposits with organic matter is interpreted as an adaptation to low oxygen levels in the upper water column (Premoli Silva et al., 1999; Coccioni et al., 2006).

Moreover, the occurrence of radiolarians and pyrite framboids, as well as an increasing supply of nutrients, suggests oxygen depletion in the paleoenvironment recognized during the Aptian and related to an anoxic event reported in this interval (Bralower et al.,1999; Leckie et al., 2002; Khan et al., 2021).

The anoxic conditions during the Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone revealed in this research are the local expression of the so called “late Aptian anoxic event” first reported by Bralower et al. (1999) in the Santa Rosa Canyon section, NE Mexico. There corresponds to an organic-rich interval. This event has been also identified by Kochhann et al. (2013) in cores 42-39 at DSDP Site 364 (South Atlantic Ocean), associated to the occurrence of black shale levels or even with the conditions that led to the formation of the Niveau Fallot 4 in the Vocontian basin (SE France; Friedrich et al., 2003; Herrle et al., 2004), and the black-shale-mudstone interval identified at NW Iran (Yilmaz, 2008) , also the studied succession could be correlate in part with the Thalmann Event identified in the San Francisco Complex of northern California, USA (Sliter, 1989a;1999).

Radiolarian-rich facies within the Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone have also been recently documented by Gutiérrez-Puente et al. (2021) in the Linderos section, central eastern Mexico, which reinforce the idea of upwelling along the western margin of the Gulf of Mexico during Aptian time.

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

The species identified in this study are described and the synonymies are constrained to the references applicable to knowledge on the foraminifera in thin sections. The thin sections are housed in the Paleontology Collection of the Institute of Geology (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). The stratigraphic range of the described species has been transcribed from pforams@mikrotax.

Supergroup Rhizaria Cavalier-Smith, 2002

Class Foraminifera d’Orbigny, 1826

Order Globigerinina Delage and Hérouard, 1896

Family Globigerinelloididae Longoria, 1974

Subfamily Globigerinelloidinae Longoria, 1974

Genus Globigerinelloides Cushman and ten Dam, 1948

Type species. Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and ten Dam, 1948.

Globigerinelloides algerianus Cushman and Ten Dam, 1948 (Figure 3a, 3b, 3d, 3e)

Globigerinelloides algeriana Cushman and Ten Dam, 1948, p. 43, pl. 8, figs 4–6; Sliter, 1989b, p. 13, pl. 1, figs. 13-14; Sliter, 1992, p. 288, fig. 6 (1); Sliter, 1999, p. 334, pl. 2, figs. 17-18; Premoli Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 324, pl. 157, figs. 13-14; Mandic and Lukeneder, 2008, p. 906, fig. 7 (9).

Description. Test large, planispirally coiled, periphery broadly rounded; chambers globular, 10-12 in last whorl, increasing gradually and evenly in size as added; sutures depressed, in the earlier stages nearly radial, later somewhat arched; wall calcareous, finely perforate, the surface relatively rugose, showing dark and light layers in thin section; aperture a small, arched opening in the median line at the base of the apertural face.

Stratigraphic range. First and last occurrence in the G. algerianus Zone (Aptian stage).

Globigerinelloides aptiensis Longoria, 1974 (Figure 3j)

Globigerinelloides aptiense Longoria, 1974, p. 79, pl. 4, figs. 9–10, pl. 8, figs. 4–6, 17, 18. Globigerinelloides aptiensis; Sliter, 1999, p. 334, pl. 2, figs. 8-9; Premoli-Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 239, pl. 9, fig. 6; Blowiella aptiensis (Longoria) Mandic and Lukeneder, 2008, p. 906, fig. 7(5).

Description. Test small, planispiral, biumbilicate, peripheral outline subcircular lobate, with five to six globular chambers in the last whorl increasing gradually in size as added, sutures radial and depressed; relict apertures and flaps could be observed.

Remarks. Globigerinelloides aptiensis differs from Globigerinelloides blowi by having more numerous chambers in the last whorl and slow growth rate resulting in a lobate test. The spiral view of the specimen observed is comparable to the illustration of Premoli-Silva and Verga (2004).

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Globigerinelloides blowi (base in Barremian stage); last occurrence within Paraticinella rohri (top in Aptian stage).

Globigerinelloides barri (Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957) (Figures 3g, 3h)

Biglobigerinella barri Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957, p. 25, pl.1, figs. 13-18; Globigerinelloides barri (Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan); Longoria,1974, p. 80-82, pl.4, figs. 1-3, 8, 14, pl. 5, figs. 9-16; Sliter, 1992, p. 288, fig. 6(2); Sliter, 1999, p. 334, pl. 2, fig. 20; Mandic and Lukeneder, 2008, p. 906, fig. 7(10).

Description. Test planispiral, biumbilicate, nearly involute to evolute; peripheral margin somewhat lobulate; chambers ovate to nearly spherical; in some specimens a smaller low but broad final chamber may cover a double-apertured penultimate chamber or there may be a small chamber at each side of the periphery; wall calcareous, finely perforate, surface distinctly rugose; aperture equatorial, a low arch bordered above with a narrow lip; in the later stage there is a double aperture consisting of a small extraumbilical arch at each side of the last chamber, or one to each of the final paired chambers which may extend almost into the umbilicus.

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Globigerinelloides blowi Zone (base in the Barremian stage); last occurrence within G. algerianus Zone (top in Aptian stage).

Globigerinelloides ferreolensis (Moullade, 1961) (Figures 3c, 3f)

Biticinella ferreolensis Moullade, 1961, p. 214, pl. 1, figs 1–5. Globigerinelloides ferreolensis (Moullade) Moullade, 1966, p. 123, pl. 9, figs. 1–3; Sliter, 1989b, p. 13, pl. 1, figs. 11, 12; Sliter, 1992, p. 288, figs. 6 (5,6); Sliter, 1999, p. 334, pl. 2, fig. 19; Premoli Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 239, pl. 9, figs. 12-15; Mandic and Lukeneder, 2008, p. 906, fig. 7 (7).

Description. Planispiral test, perforate, slightly compressed, chambers increasing in size gradually from small chambers in early whorls and larger chambers in final whorl, with 7-9 globular chambers; wall relatively thick.

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Leupoldina cabri Zone (base in the Aptian stage); last occurrence within Ticinella bejaouaensis Zone (top in Aptian stage).

Family Planomalinidae Bolli, Loeblich and Tappan, 1957

Genus Pseudoplanomalina Moullade, Bellier, Tronchetti, 2002

Type species. Planulina cheniourensis Sigal, 1952.

Pseudoplanomalina cheniourensis (Sigal, 1952) (Figures 4a, 4b)

Planulina cheniourensis Sigal 1952, p. 20, fig. 17): Sliter, 1992; p. 288, fig, 6 (10-11); Sliter, 1999, p. 334, pl. 2, fig. 27; Pseudoplanomalina cheniourensis (Sigal) Moullade, et al., 2002, p. 130- 131, fig. 3; Premoli Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 264, pl. 34, figs. 1-5.

Description. Test compressed planispiral, bi-evolute, with typically diamond-shaped chambers and angular profile in transverse section with a distinct break in the peripheral round, better marked on the first chambers of the last whorl forming a peripheral pseudo-keel.

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Leupoldina cabri Zone (base in the Aptian stage); last occurrence within Hedbergella planispira Zone (top in Albian stage).

Family Hedbergellidae Loeblich and Tappan, 1961

Subfamily Hedbergellinae Loeblich and Tappan, 1961

Genus Hedbergella Brönnimann and Brown, 1958.

Type species. Anomalina lorneiana d'Orbigny var. trochoidea Gandolfi, 1942.

Hedbergella luterbacheri Longoria, 1974 (Figure 3k)

Hedbergella luterbacheri Longoria, 1974, p. 61, pl.19, figs. 21-23, 24-26; pl. 26, figs. 15-17; Premoli-Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 239, pl. 9, fig. 6

Description. Medium-sized, test coiled in a low trochospire, formed by about 3 whorls, peripheral margin circular, chambers spherical in axial view; umbilicus wide.

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Hedbergella similis Zone (base in Barremian stage); last occurrence within Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone (top in Aptian stage).

Hedbergella roblesae (Obregón de la Parra, 1959) (Figure 4c)

Globigerina roblesae Obregón de la Parra, 1959 , p. 149, pl. 4, fig. 4. Hedbergella roblesae (Obregón de la Parra) Longoria, 1974, p. 65, pl. 16, figs 1–6; pl. 20, figs 10, 11; Premoli Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 251, pl. 21, figs. 6-8; Clavihedbergella roblesae (Obregón de la Parra), Sliter, 1999, p. 335, pl. 3, figs. 7-8.

Description. Trochospiral test, the peripheral margin is lobate; spiral side low to medium-high; the first chambers are globular, the last 3 are elongate; sutures straight on spiral side; the wall texture is calcareous, finely perforated, smooth.

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Hedbergella similis Zone (in Barremian stage); last occurrence within Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone (top in Aptian stage).

Hedbergella similis Longoria, 1974 (Figure 4d)

Hedbergella similis Longoria, 1974, p. 68, pl. 16, figs. 10–21, pl. 18, figs. 12, 13, pl. 23, figs. 14–16; Sliter, 1992, p. 290, fig. 7(6-7); Sliter, 1999, p. 335, pl. 3, figs. 6, 13.

Description. Test small to medium trochospirally coiled, with 2–3 whorls composed of five to six chambers in the last whorl globular then elongate, gradually increasing in size; peripheral margin lobate, sutures radial, slightly curved, on both umbilical and spiral sides; sutures radial, slightly curved, relict apertures commonly observed on spiral side.

Remarks. Hedbergella similis is differentiated from Hedbergella semielongata by having a depressed inner spire and more chambers in the last whorl.

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Hedbergella similis Zone (base in Barremian stage); last occurrence within Globigerinelloides algerianus Zone (top in Aptian stage).

Hedbergella semielongata Longoria,1974 (Figure 4e)

Hedbergella semielongata Longoria, 1974, Longoria, 1974, p. 66, pl. 20, figs. 12-13, pl. 21, figs. 1-3, 4-5; Premoli Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 251, pl. 21, figs. 9-10.); Clavihedbergella semielongata Sliter,1999, p. 335, pl. 3, fig. 12.

Description. Test trochospirally coiled; 4 chambers in the outer whorl, chambers firstly globular to subglobular, the last two radially elongate; spiral side relatively high; peripheral outline cross-shaped; sutures straight to slightly curved on both spiral and umbilical sides. Stratigraphic range. First occurrence (base) within H. similis Zone (base in Barremian stage); last occurrence (top) within G. algerianus Zone (top in Aptian stage). Wall smooth and finely perforate.

Hedbergella occulta Longoria, 1974 (Figure 4f)

Hedbergella occulta Longoria, 1974, p. 63, 64, pl. 11, figs. 1–3, 7, 8, pl. 20, figs. 5–7, 8, 9, 17, 18; Premoli-Silva and Verga, 2004, p. 251, pl. 21, fig. 3; Praehedbergella occulta Mandic and Lukeneder, 2008, p. 906, fig. 7(11).

Description. Test medium in size, coiled in a low to moderate trochospire, chambers globular, somewhat ovoid on both spiral and umbilical sides; spherical in peripheral view; sutures radial, slightly curved on both spiral and umbilical sides; umbilicus circular, deep.

Stratigraphic range. First occurrence within Globigerinelloides blowi Zone (base in the Aptian stage); last occurrence within Ticinella bejaouaensis Zone (top in Aptian stage).

Figure 5. Microfacies of the “Otates Horizon” (early late Aptian to middle late Aptian). Scale bar 100 µm. a) Microfacies 1- Pelagic foraminiferal-radiolarian wackestone (Sample CB-1). b) Microfacies 2-Planktic Foraminiferal wackestone (Sample CB-2). c) Microfacies 3- Foraminiferal wackestone-packstone (Sample CB-4) d) Microfacies 4- Foraminiferal-radiolarian wackestone (Sample CB-6). e, f) Radiolarians (Sample CB-1) Scale bar 100 µm.

Figure 6. Photomicrographs of pyrite framboids under: a) reflected light, b) SEM, c) the foraminifer chambers filled of pyrite.

CONCLUSIONS

We identified and described in thin section the most important species of planktic foraminifera included in the studied samples from Cerro Boludo, Hidalgo.

Based on the foraminiferal assemblage, the Globigerinelloides algerianus Total Range Zone of the early late-middle late Aptian age was recognized.

The studied dark marly limestone samples of wackestone texture contain an assemblage characterized by planktic foraminifera suggesting a pelagic open-marine environment. Moreover, presence of pyrite framboids and the organic matter deposit indicate depleted oxygen conditions which correlate with the local anoxic events described in other locations that took place during the late Aptian.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the Instituto de Geología of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for supporting this study. We thankful to Dra. Ana Bertha Villaseñor (UNAM) for providing the samples and the information of the locality.We thank to the anonymous reviewer and Dr. Carmen Rosales (Independent Research) for their useful comments and remarks that much improved the manuscript.We are deeply grateful to the Editor in Chief Dr. Angel F. Nieto Samaniego (Centro de Geociencias, UNAM, Mexico) for his careful handling of our paper. We thank to Ing. J Jesús Silva Corona Technical Editor (Centro de Geociencias, UNAM Juriquilla, México) for the final review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Belt, B.C., 1925, Stratigraphy of the Tampico District of Mexico: Bulletin American Association of Petroleum Geologist, 9 (1), 136-144.

Bodenlos, A.J., 1956, Notas sobre la geología de la Sierra Madre en la sección Zimapán- Tamazunchale, in Estratigrafía del Cenozoico y del Mesozoico a lo largo de la carretera entre Reynosa, Tamaulipas. y México, D.F. Tectónica de la Sierra Madre Oriental. Vulcanismo en el Valle de México. XX Congreso Geológico Internacional., México, D.F., Libreto-guía, Excursiones A-14 y C-6, 323 p., mapas y tablas.

Bolli, H.M., 1959, Planktonic foraminifera from the Cretaceous of Trinidad, B. W.I.: Bulletins of American Paleontology, 39 (179), 257-277.

Bolli, H. M., Loeblich, A. R., Tappan, H., 1957, Planktonic foraminiferal families Hantkeninidae, Orbulinidae, Globorotaliidae and Globotruncanidae, in Loeblich, A.R., Jr., Tappan, H., Beckmann, J.P., Bolli, H.M., Montanaro Gallitelli, E. Troelsen, J.C. (eds.), Studies in Foraminifera: U.S. National Museum Bulletin, 215, 3-50.

Bottini, C., Erba, E., Tiraboschi, D., Jenkyns, H.C., Schouten, S., Sinninghe Damsté, J., 2015, Climate variability and ocean fertility during the Aptian Stage: Climate of the Past, 11, 383-402.

Bralower, T. J., Cobabe, E., Clement, B., Sliter, W.V., Osburn, C.L., Longoria, J.F., 1999, The record of global change in mid-Cretaceous (Barremian–Albian) sections from the Sierra Madre, northern Mexico: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 29, 318-437.

Brönnimann, P., Brown, J.N.K., 1958, Hedbergella, a new name for a Cretaceous planktonic foraminiferal genus: Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 48(1), 15-17.

Burckhardt, C., 1930, Etude synthétique sur le Mésozoïque Mexicain: Mémoires de la Société Paléontologique Suisse, 280 pp.

Caron, M., 1985, Cretaceous Planktonic Foraminifera, in Bolli, H.M., Saunders, J.B., Perch-Nielsen, K. (eds.), Plankton Stratigraphy: Cambridge University Press, 17-86.

Carrillo-Bravo, J., 1961, Geología del Huizachal-Peregrina anticlinorio al Noroeste de Ciudad. Victoria, Tamaulipas: Boletín de la Asociación Mexicana de Geólogos Petroleros, 13 (1-2), 1-98.

Cavalier-Smith, T., 2002, The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa: International Journal of Systematics and Evolutionary Microbiology, 52, 297-354.

Chávez Cabello, G., Torres Ramos J.A., Porras Vázquez, N.D., Cossio Torres, T., Aranda Gómez, J.J., 2011, Evolución estructural del frente tectónico de la Sierra Madre Oriental en el Cañón Santa Rosa, Linares, Nuevo León: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 63(2), 253-270.

Coccioni, R., 2020, Revised upper Barremian-upper Aptian planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy of the Gorgo a Cerbara section (central Italy): Newsletters on Stratigraphy, 53(3), 275-295.

Coccioni, R., Erba, E., Premoli-Silva, I., 1992, Barremian Aptian calcareous plankton biostratigraphy from the Gorgo Cerbara section (Marche, central Italy) and implications for plankton evolution: Cretaceous Research, 13, 517-537.

Coccioni, R., Luciani, V., Marsili, A., 2006. Cretaceous anoxic event and radially elongate chambered foraminifera: paleoecological and paleoceanographic implications: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 235, 66-92.

Cushman, J.A., Ten Dam, A., 1948, Globigerinelloides, a new genus of the Globigerinidae: Contributions from the Cushman Laboratory for Foraminiferal Research, 24(2), 42-43.

Delage, Y., Hérouard, E., 1896, Traité de Zoologie Concrète, vol. 1, La Cellule et les Protozoaires: Paris, Schleicher Frères, 584 pp.

Enos, P., 1974, Reefs, platforms, and basins of middle Cretaceous in northeast Mexico: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 58(5), 800-809.

Erba, E., Duncan, R.A., Bottini, C., Tiraboschi, D., Weissert, H., Jenkyns, H.C., Maliverno, A., 2015, Environmental consequences of Ontong Java Plateau and Kerguelen Plateau volcanism: The Geological Society of America, Spécial Paper 511, 271-303.

Flügel, E., 2010, Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks. Analysis, Interpretation and Application: Germany, Springer, 976 pp.

Föllmi, K.B., 2012, Early Cretaceous life, climate and anoxia: Cretaceous Research, 35, 230-257.

Friedrich, O., Reichelt, K., Herrle, J.O., Lehmann, J., Pross, J., Hemleben, C., 2003, Formation of the Late Aptian Niveau Fallot black shales in the Vocontian Basin (SE France): evidence from foraminifera, palynomorphs, and stable isotopes: Marine Micropaleontology, 49(1), 65-85.

Gamper, M.A., 1977, Estratigrafía y microfacies Cretacicas del Huizachal-Peregrina anticlinorium (Sierra Madre Oriental): Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 38 (2), 1-17.

Gandolfi, R., 1942, Ricerche micropaleontologiche e stratigraphfiche sulla Scaglia e sul flysch Cretacici dei Dintorni di Balerna (Canton Ticino): Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia, 48, 1-160.

Gutiérrez Puente, N., Barragán, R., Nuñez Useche, F., 2021, Paleoenvironmental changes and biotic response to Aptian–Albian episodes of accelerated global change: Evidence from the western margin of the proto-North Atlantic (central-eastern Mexico): Cretaceous Research, 126, 104883.

Hart, M.B., 1999, The evolution and biodiversity of Cretaceous planktonic Foraminiferida: Geobios, 32 (2), 247-255.

Heim, A., 1926, Notes on the Jurassic of Tamazunchale (Sierra Madre Oriental, México): Eclogae Geologica Helvetiae, 20(1), 84-87.

Herrle J.O., Köbler P., Friedrich, O., Erlenkeuser H., Hemleben C. 2004, High-resolution carbon isotope records of the Aptian to Lower Albian from SE France and the Mazagan Plateau (DSDP Site 545): a stratigraphic tool for paleoceanographic and paleobiologic reconstruction: Earth and Planetary Science Letters 218, 149-161.

Hosseini, S.A., Conrad, M.A., 2010, Evidence for an equivalent of the late Aptian Oceanic Anoxic Event (OAE) across the Kazerun Fault, SW Iran, in 1st International Applied Geological Congress: Ira, Department of Geology, Islamic Azad University of Mashad, 26-28.

Humphrey, W.E., Díaz, T., 1956, Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous Stratigraphy and tectonics of Northeast México: Petróleos Mexicanos, unpublished report, NE-M 799, 156 pp.

Imlay, R.W.,1944, Cretaceous formations of the Central America and Mexico: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 28, 1077-1195.

Jenkyns, H,C., 2010, Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events: Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems, 11(1), 1-30.

Khan, S., Kron, D., Wadood, B., Ahmad, S., Zhou, X., 2021, Marine depositional signatures of the Aptian Oceanic Anoxic Events in the Eastern Tethys, Lower Indus Basin, Pakistan: Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. DOI: 10.1080/08120099.2021.1959399

Kochhann, K., Koutsoukus, E., Fauth, G., Sial, A., 2013, Aptian -Albian planktic foraminifera from DSDP SITE 364 (Offshore Angola): Biostratigraphy, Paleoecolgy and Palaeoceanographic significance: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 43 (4), 443-463.

Kretschmer, K., Jonkers, L., Kucera, M., Schulz, M., 2018, Modeling seasonal and vertical habitats of planktonic foraminifera on a global scale: Biogeosciences, 15, 4405-4429.

Kuroyanagi, A., Kawahata, H., Ozaki, K., Suzuki, A., Nishi, H., Takashima R., 2020, What drove the evolutionary trend of planktic foraminifers during the Cretaceous: Oceanic Anoxic Events (OAEs) directly affected it?: Marine Micropaleontology, 161, 101924.

Leckie, R.M., Bralower, T.J., Cashman, R., 2002, Oceanic anoxic events and plankton evolution: biotic response to tectonic forcing during the mid-Cretaceous: Paleoceanography, 17, 1-29.

Lehmann, C., Osleger, D.A., Montañez, I.P., Sliter, W., Arnaud-Vanneau, A., Banner, J.,1999, Evolution of Cupido and Coahuila carbonate platforms, Early Cretaceous, northeastern Mexico: Geological Society of America Bulletin, 111 (7), 1010-1029.

Lipps, J., 1979, Ecology and Paleoecology of Planktic foraminifera, in Lipps, J.H., Berger, W.H., Buzas, M.A., Douglas, R.G., Ross, C.A. (eds) Foraminiferal Ecology and Paleoecology: SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology, vol. 6, 62-104, https://doi.org/10.2110/scn.79.06

Loeblich, A.R.; Tappan, H., 1961, Cretaceous planktic foraminifera: Part I-Cenomanian: Micropaleontology, 7, 257-304.

Longoria, J.F., 1974, Stratigraphic, morphologic and taxonomic studies of Aptian planktonic foraminifera: Revista Española de Micropaleontología. Número Extraordinario, 107 pp.

Longoria, J.F., 1975, Estratigrafía de la Serie Comancheana del Noreste de México: Boletín de la Asociación Mexicana de Geólogos Petroleros, 36(1), 1-17.

Longoria, J.F., 1984, Cretaceous biochronology from the Gulf of Mexico region based on planktonic microfossils: Micropaleontology, 30, 225-242.

Magniez-Jannin, F., 1998, L'élongation des loges chez les foraminifères planctoniques du Crétacé Inférieur : une adaptation à la sous oxygénation des aux?: Comptes Rendus Académie Sciences Paris, Sciences de la Terra et des Planètes, 326, 207-213.

Mandic, O., Lukeneder, A., 2008, Dating the Penninic Ocean subduction: new data from planktonic foraminifera: Cretaceous Research, 29, 901-912.

McFarlan, E. Jr., Menes, L.S., 1991, Lower Cretaceous, in Salvador, A. (ed.), The Gulf of Mexico Basin: Geological Society of America, The Geology of North America, J, 181-204.

Moullade, M., 1961, Quelques foraminifères et ostracodes nouveaux du Crétacé inférieur Vocontien: Revue de Micropaléontologie, 3(4), 213-216.

Moullade, M., 1966, Etude stratigraphique et micropaléontologique du Crétacé Inférieur de la Fosse Vocontienne: Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de la Faculté des Sciences de Lyon, 15, 1-369.

Moullade, M., Bellier, J.P., Tronchetti, G., 2002, Hierarchy of criteria evolutionary processes and taxonomic simplification in the classification of Lower Cretaceous planktonic foraminifera: Cretaceous Research, 23, 111-114.

Muir, J.M., 1936, Geology of Tampico region, Mexico: Tulsa Oklahoma, American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, , 280 pp.

Obregón de la Parra, J., 1959, Consideraciones sobre el Daniano en la Cuenca sedimentaria de Tampico-Misantla: Boletín de la Asociación Mexicana de Geólogos Petroleros, 11(1-2), 13-20.

Orbigny, A.D. d'., 1826, Tableau méthodique de la classe des Céphalopodes: Annales des Sciences Naturelles, 7, 96-314.

Premoli Silva, I., Sliter, W.V., 1995, Cretaceous planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy and evolutionary trends from the Bottaccione section, Gubbio, Italy: Paleontographia Italica, 82, 1-89.

Premoli Silva, I., Sliter, W.V., 1999, Cretaceous paleoceanography: Evidence from planktonic foraminiferal evolution, in Barrera E., Johnson C.C. (eds.), Evolution of the Cretaceous Ocean-Climate System: Special Paper Geological Society of America, 332, 301-328.

Premoli Silva, I., Verga, D., 2004, Practical Manual of Cretaceous Planktonic Foraminifera, in Verga, D., Rettori, R. (eds.), International School on Planktonic Foraminifera. 3o Course: Cretaceous: Perugia, Italy, Universities of Perugia and Milan. Tipografia Pontefelcino, 283 pp.

Price, G.D., Hart, M.B., 2002, Isotopic evidence of Early to mid-Cretaceous Ocean temperature variability: Marine Micropaleontology, 46, 45-58.

Premoli Silva, I., Erba, E., Salvini, G., Verga, D., Locatelli, C., 1999, Biotic changes in Cretaceous anoxic events: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 29, 352-370.

Robaszynski, F., Caron, M., 1995, Foraminifères planctoniques du Crétacé: commentaire de la zonation Europe-Méditerranée: Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 166 (6), 681-692.

Ross M.A., McNulty C.L., 1981, Some microfossils of the Tamaulipas Limestone (Hauterivian-Lower Albian) in Santa Rosa Canyon, Sierra de Santa Rosa, Nuevo Leon, Mexico : Gulf Coast Association of Geological Societies Transactions, 31, 461-469.

Schacko, G., 1897, Beitrag über Foraminiferen aus der Cenoman-Kreide von Moltzow in Mecklenburg: Archiv des Vereins der Freunde der Naturgeschichte in Mecklenburg, 50, 161-168.

Schiebel, R., Waniek, J., Bork, M., Hemleben, C., 2001, Planktic foraminiferal production stimulated by chlorophyll redistribution and entrainment of nutrients: Deep Sea Research Part I Oceanographic Research Papers, 48(3), 721-740.

SGM (Servicio Geológico Mexicano), 2004, Carta Geológico-Minera Chapulhuacán F14-D41, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, escala 1:50,000: Pachuca, Hidalgo, Secretaría de Economía, 1 mapa.

Sigal, J., 1952. Aperçu stratigraphique sur la micropaléontologie du Crétacé, in XIX Congres Géologique International: Algérie, Monographies regionales, 26, 1-47.

Sliter, W.V., 1989a, Aptian anoxia in the Pacific Basin: Geology, 17, 909-912.

Sliter, W.V., 1989b, Biostratigraphic zonation for Cretaceous planktonic foraminifers examined in thin sections: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 19(1), 1-19.

Sliter, W.V., 1992, Cretaceous planktonic foraminniferal biostratigraphy and paleoceanographic events in the Pacific Ocean with emphasis on indurated sediment, in Ishizaki, K., Saito, T. (eds.), Centenary of Japanese Micropaleontology: Tokyo, Terra Scientific Publishing Company, 281-299.

Sliter, W.V., 1999, Cretaceous planktic foraminiferal biostratigraphy of the Calera Limestone, Northern California, USA: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 29(4), 318-339.

Tarduno, J.A., Sliter, W.V., Kroenke L., Leckie, M., Mayer, R.H., Mahoney, J.J., Musgrave, R., Storey, M., Winterer, E.L., 1991, Rapid Formation of Ontong Java Plateau by Aptian Mantle Plume Volcanism: Science, 254, 791-795.

Wignall, P.B., Newton, R., Brookfield, M.E., 2005, Pyrite framboid evidence for oxygen- poor deposition during the Permian–Triassic crisis in Kashmir: Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 216, 183-188.

Wilkin, R.T., Barnes, H.L., Brantley, S.L., 1996, The size distribution of framboidal pyrite in modern sediments: An indicator of redox conditions: Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta, 6, 3897-3912.

Wilson, J.L., 1975, Carbonate Facies in Geologic History: New York, Springer Verlag, 449 pp.

Yilmaz, S.Ö., 2008, Cretaceous Pelagic Red Beds and Black Shales (Aptian-Santonian), NW Turkey: Global Oceanic Anoxic and Oxic Events: Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences, 17, 263-296.

Žaric, S., Donner, B., Fischer, G., Mulitza, S., Wefer, G., 2005, Sensitivity of planktic foraminifera to sea surface temperature and export production as derived from sediment trap data: Marine Micropaleontology, 55, 75-105.