ABSTRACT

During the Maastrichtian, two lithostratigraphic units were deposited in the central Chiapas region; the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations. The first unit crops out northwest of the city of Tuxtla Gutiérrez in central Chiapas. It is a complex lithological unit mainly composed of siliciclastic rocks interbedded with limestone. Overlying it, the Angostura limestone is recognized. This study focuses on a taxonomic study of the larger benthic and planktic foraminifera from both formations in order to assign age and to infer the paleoenviroment.

The Ocozocoautla Formation includes an association of benthic as well as significant planktic foraminifera. Based on the microfossils stratigraphic distribution, two biozones were defined: the Pseudorbitoides rutteni–Ayalaina rutteni Assemblage Zone of earliest Maastrichtian and the upper part of the Gansserina gansseri Interval Zone of early Maastrichtian.

The Angostura Formation contains dasycladacean algae and larger foraminifera considered as important age markers in shallow-water environments. Two foraminiferal interval zones were defined, Praechubbina breviclaustra Interval Zone of early late Maastrichtian and Chubbina jamaicensis Total Range Zone of late to latest Maastrichian age.

The microfacies (grainstone, wackestone–packstone, wackestone) as well as the foraminiferal assemblage enable the paleoenvironment to be reconstructed, suggesting a deposit that developed in an open-water marine setting with moderate to high energy, characterized by benthic and planktic foraminifera in the Ocozocoautla Formation, while in the Angostura Formation a shallow-water marine protected environment is inferred.

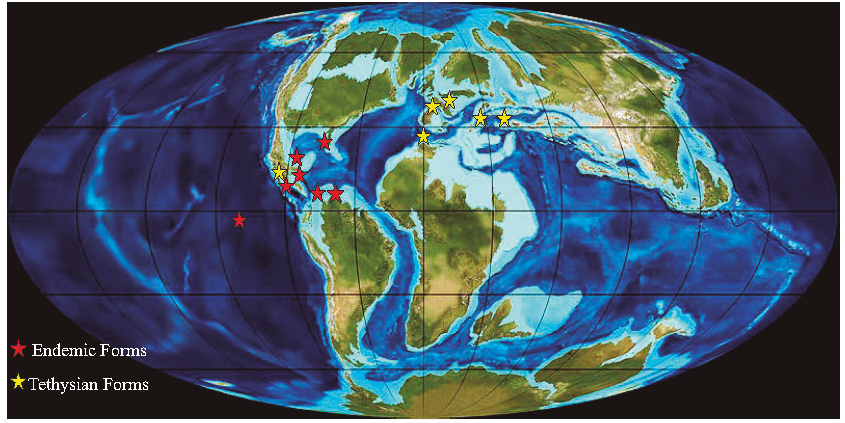

The paleobiogeographical distribution of the assemblage from both the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations mostly contains endemic benthic foraminifera of the Caribbean Province and other few Tethysian forms of the Angostura Formation.

Key words: Foraminifera; early–late Maastrichtian; Chiapas; SE Mexico.

RESUMEN

Durante el Maastrichtiano se depositaron dos unidades litológicas en el centro de Chiapas, las formaciones Ocozocoautla y Angostura. La primera unidad está aflorando al noroeste de la ciudad de Tuxtla Gutiérrez, en el centro de Chiapas. Es una unidad litológica compleja compuesta principalmente de rocas siliciclásticas interestratificadas con caliza. Sobreyaciendo a esta unidad se reconoce a la caliza Angostura. Esta investigación se ha centrado en el estudio taxonómico de los macroforaminíferos de ambas formaciones y en la presencia de foraminíferos planctónicos del componente calcáreo de la unidad Ocozocoautla.

La Formación Ocozocoautla incluye una asociación de foraminíferos bentónicos, así como importantes foraminíferos planctónicos, con base en la distribución estratigráfica de estos microfósiles fueron definidas dos zonas Zona de Conjunto Pseudorbitoides rutteni–Ayalaina rutteni del Maastrichtiano más temprano y la parte superior de la Zona de Intervalo Gansserina gansseri del Maastrichtiano temprano.

Por otro lado, la Formación Angostura contiene macroforaminíferos, los cuales son considerados importantes marcadores de edad en ambientes someros: dos zonas fueron definidas la Zona de Intervalo Praechubbina breviclaustra del Maastrichtiano tardío temprano y la Zona de Alcance Total Chubbina jamaicensis del Maastrichtiano tardío a más tardío.

Las microfacies (grainstone, wackestone–packstone,wackestone), así como el conjunto foraminiferal permiten reconstruir el paleoambiente, sugiriendo un depósito que se desarrolló en un entorno marino de aguas abiertas con energía moderada a alta, caracterizado por foraminíferos planctónicos para la Formación Ocozocooautla mientras que en la Formación Angostura se infiere un ambiente protegido de aguas poco profundas. La distribución paleobiogeográfica del conjunto foraminiferal de las formaciones Ocozocoautla y Angostura contienen principalmente formas endémicas de la Provincia del Caribe, así como otras pocas formas Tethysianas en la Formación Angostura.

Palabras clave: Foraminíferos; Maastrichtiano temprano–tardío; Chiapas; SE de México.

Manuscript received: november 9, 2020

Corrected manuscript received: february 15, 2021

Manuscript accepted: february 18, 2021

INTRODUCTION

The studied foraminiferal assemblage in the Chiapas Central Depression was sampled west of Ocozocoautla town in rocks of the Ocozocoautla Formation and Angostura Formation. Here the Ocozocoautla Formation unconformably overlies the Suchiapa Formation, differentiated by Michaud (1987) on top of the predominantly Early and mid-Cretaceous Sierra Madre Formation. The Ocozocoautla Formation is composed of siliciclastic rocks, quartz conglomerates in its basal proximal part changing to finer grained rocks upwards and distally, and some carbonate intercalations. Here the Angostura Formation unconformably overlies the Ocozocoautla Formation, with quartz microconglomerate intervals indicating erosion from a brief subaereal exposure and even a red argillaceous interval developed between the two formations. The Angostura Formation mainly consists of carbonate rocks with grainstone, packstone, and wackestone textures.

Macrofossils from the area are abundant and diverse: rudist bivalves have been reported from both formations (Müllerried, 1931, 1934; Chubb, 1959; Alencáster, 1971; Alencáster and Pons, 1992; Pons et al., 2016, 2019); inoceramid bivalves and/or ammonites from the Ocozocoautla Formation (Michaud, 1984; Bolaños and Buitrón, 1984; Alencáster and Omaña, 2006; Pons et al. 2016); bivalves and gastropods (Buitrón et al., 1995); corals (Filkorn et al., 2005; Löser, 2012), crustaceans (Vega et al, 2001, 2018; Hyžný et al, 2013), and vertebrate remains (Carbot-Chanona and Rivera-Sylva, 2011; Carbot-Chanona and Than-Marchese, 2013). Larger foraminifera are abundant in both the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations (Ayala-Castañares, 1963; Michaud, 1987; Rosales-Domínguez et al., 1997; Omaña and Pons, 2003; Vicedo et al., 2013). Planktic foraminifera have been reported from the beds with inoceramids of the Ocozocoautla Formation (Brönnimann in Chubb, 1959; Michaud, 1984; Omaña, 2006). The benthic and planktic foraminiferal assemblage of the Angostura Formation at the El Coyol section, in the locality type of the formation, has been reported in detail by Omaña and Alencáster (2019).

The Ocozocoautla Formation was first documented by Sapper (1894) in a geological report of the Chiapas region. The term “Gravas Ocozocoautla” was first used in an unpublished report by Page and Pike (1921). This succession was subsequently defined by Gutiérrez Gil (1956) as the “Ocozocoautla Series” and Chubb (1959) later divided it into five formations: Piedra Parada beds, San Luis Conglomerate, Nuevo beds, Campeche beds and Carretera Formation. More recently, Sánchez-Montes de Oca (1969) claimed that the division proposed by Chubb (1959) is questionable because the lithological variation corresponds to different facies within the same formation. The name of Angostura Formation was proposed by Sanchez-Montes de Oca (1969) for a shallow-water limestone section located north of the Angostura dam, 50 km SE of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas.

The objective of this work is to make a complete report of the occurrence of larger benthic foraminifera in the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations from the samples collected in the Ocozocoautla area (Tuxtla Gutiérrez basin), considering that they are a useful tool for dating shallow-water sedimentary successions as well as providing a valuable means of inferring the depositional environment together with the microfacies interpretation. In addition, a planktic foraminiferal association is analyzed to support the age assignment for the Ocozocoautla unit. The paleobiographic distribution of benthic larger foraminifera is evaluated.

GEOLOGICAL SETTING

The state of Chiapas in southeastern Mexico belongs to the Maya Block, which also includes Belize and northern Guatemala. The Maya Block is bounded to the south by the Polochic-Motagua sinistral fault system, the boundary between the North American and Caribbean plates (Fourcade et al., 1999). The geological evolution and depositional framework of this region is closely related to the opening of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico in the middle Jurassic. According to Michaud and Fourcade (1989), the Jurassic sedimentation is interpreted within the rift model. The first marine sediments, the San Ricardo Formation deposited in the Oxfordian, correspond to the syn-rift phase. A post-rift phase occurred during the Kimmeridgian, with the development of a carbonate platform (Scott, 1984; Salvador, 1991). A subsident basin, present during the Tithonian, was filled until the Neocomian. After the Neocomian regression, a new marine transgression flooded the Chiapas batholith, forming a broad Albian–Cenomanian carbonate platform (Sierra Madre Formation).

According to Michaud (1987) and Michaud and Fourcade (1989), the sedimentation in the upper Campanian–Maastrichtian occurred after the fragmentation of the middle Cretaceous platform, which gave rise to several blocks, each following a different tecto-sedimentary evolution. In the Chiapas Central Depression, a drowned block (Tuxtla Gutiérrez Block) was limited by the emerged Sierra Madre de Chiapas basement and a raised block (Angostura Block), thus constituting the Tuxtla Gutiérrez basin. This basin, deepening towards the raised Angostura Block, was filled, receiving terrigenous material from the emerged Sierra Madre. Over the limestone on top of the Sierra Madre Formation (Suchiapa Formation), conglomerate, sandstone, and sandy marl were deposited landwards (Ocozocoautla Formation), while pelagic limestone (Jolpabuchil Formation) was deposited basin-wards, including calcareous breccia close to the raised Angostura Block. At the upper part of the Ocozocoautla Formation, a rudist-bearing limestone horizon was followed by a coarse terrigenous input, and a marginal shallow carbonate platform (Ocuilapa Platform, Angostura Formation) was installed above, surrounded by a belt of cross-bedded sandy bioclastic limestone (Juan Crispín Formation) prograding basin-wards on the Ocozocoautlaand Jolpabuchil formations. On the raised Angostura Block, an insular shallow carbonate platform (Angostura Platform, Angostura Formation) was installed directly above the Sierra Madre Formation (Suchiapa Formation); a bauxite interval commonly occurs at the boundary (Pons et al., 2016).

The Ocozocoautla Formation (in the Tuxtla Gutiérrez Block) and the Angostura Formation (although in the Angostura Block) unconformably overlie the Sierra Madre Formation (Suchiapa Formation). The two formations were erroneously considered lateral equivalents and were supposedly interfingering each other (Sánchez-Montes de Oca, 1969; Mandujano Velasquez and Vázquez Meneses, 1996). The biostratigraphic data in Pons et al. (2016) definitively cleared up the issue; the Angostura Formation is younger than the Ocozocoautla Formation in this area.

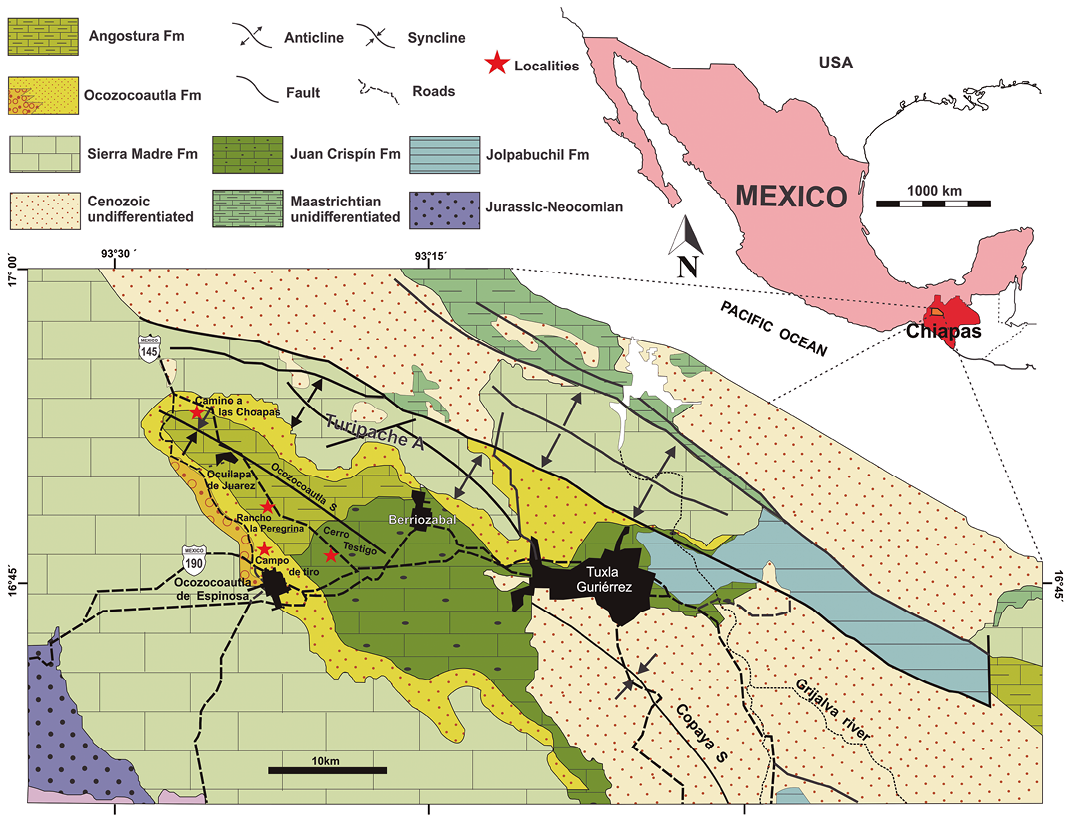

Figure 1. Geological map showing the localities studied (Modified from Pons et al., 2016).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The 20 samples used in this study were collected during a survey revisiting the rudist localities of the Upper Cretaceous in the Chiapas Central Depression (Figure 1). In the Campo de Tiro section (16°46'55.41'' N, 93°22'52.49'' W), in the Cuesta NW of Ocozocoautla, samples P-740 to P-743 were collected close below the rudist horizon, characterizing the middle rudist assemblage in Pons et al. (2016. p. 217) in the Ocozocoautla Formation; sample P-744, 70 m up-section, already corresponds to the base of the Angostura Formation. Sample P-754, Ocozocoatla Formation, was collected at Camino a las Choapas (16°53'22.27'' N, 93°25'35.72'' W), at km 178.2 on Highway 145 from Ocozocoautla to las Choapas. At Rancho La Peregrina (16°48'38.12'' N, 93°22'11.27'' W), at km 189 on Highway 145 from Ocozocoautla to las Choapas, samples P-745 to P-747, P-760 were collected, corresponding to the upper rudist assemblage in Pons et al. (2016, p. 217), Angostura Formation. At Cerro Testigo (16°46'33.49'' N, 93°19'23.37'' W), at km 195.5 on Highway 145 from Ocozocoautla to las Choapas, samples P-749, P-750, P-752, P-753, P-755, P756, P-758, P-759, P-762 were collected, corresponding to the upper rudist assemblage in Pons et al. (2016), Angostura Formation (Figure 2).

The 20 samples, marl and limestone, were processed and analyzed by means of 40 thin sections. The study of both the larger benthic and the planktic foraminifera are well preserved, allowing their identification age assignment according to the planktic zonal schemes for tropical regions (Premoli Silva and Sliter, 1995; Premoli Silva and Verga, 2004, Butterlin, 1981) microfacies and the benthic foraminiferal association enabled the paleoenvironment interpretation following to Flügel (2010). Paleobiogeographic distribution of these microfossils was also reviewed.

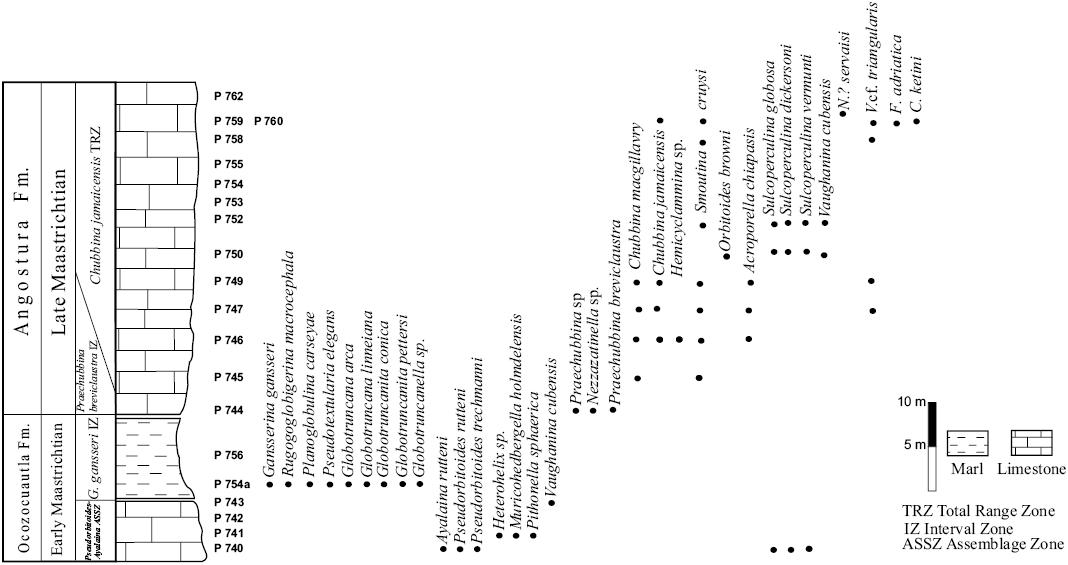

Figure 2. Schematic section of the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations.

RESULTS

Foraminiferal assemblage

Ocozocoautla Formation

The limestone samples collected from the Ocozocoautla Formation contain orbitoidal larger benthic foraminifera such as Pseudorbitoides rutteni Brönnimann, P. trechmanni Douvillé, Ayalaina rutteni (Palmer) also Sulcoperculina dickersoni (Palmer), S. vermunti (Thiadens), S. globosa de Cizancourt, Nezzazatinella picardi (Henson).

The planktic foraminifera are diversified and significant from the biostratigraphic point of view, being Gansserina gansseri (Bolli), Contusotruncana walfishensis (Todd), Globotruncana arca (Cushman), G. bulloides Vogler, G. linneiana (d'Orbigny), Globotruncanita conica (White), G. pettersi (Gandolfi), Rugoglobigerina macrocephala Brönnimann, R. hexacamerata Brönnimann, Muricohedbergella holmdelensis (Olsson), Planoglobulina carseyae (Plummer), Pseudotextularia elegans (Rzehak), Globotruncanella sp., Pithonella sphaerica (Kaufmann, 1865).

Angostura Formation

The Angostura Formation includes a benthic foraminiferal association composed of Praechubbina breviclaustra Fourcade and Fleury, Praechubbina oxchucencis Vicedo et al., Orbitoides browni (Ellis), Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, C. macgillavryi Robinson, Smoutina cruysi Drooger, Valvulina cf. V. triangularis d'Orbigny, Cuneolina ketini Inan, Fleuryana adriatica De Castro, Drobne and Gušić, Vaughanina cubensis Palmer. In addition, the dasycladacean algae Acroporella chiapasis Deloffre, Fourcade and Michaud and Neogyroporella? servaisi Michaud.

Biostratigraphy

The biostratigraphic significance of the planktic foraminifera, as well as of the larger benthic foraminifera, is widely recognized, as they are an important tool for dating marine sedimentary rocks, so they enable us to assign an age to the samples studied.

We identified the following zones from the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations (Figure 2).

Pseudorbitoides rutteni–Ayalaina rutteni Assemblage Zone (Ocozocoautla Formation, Sample P-740–P-743)

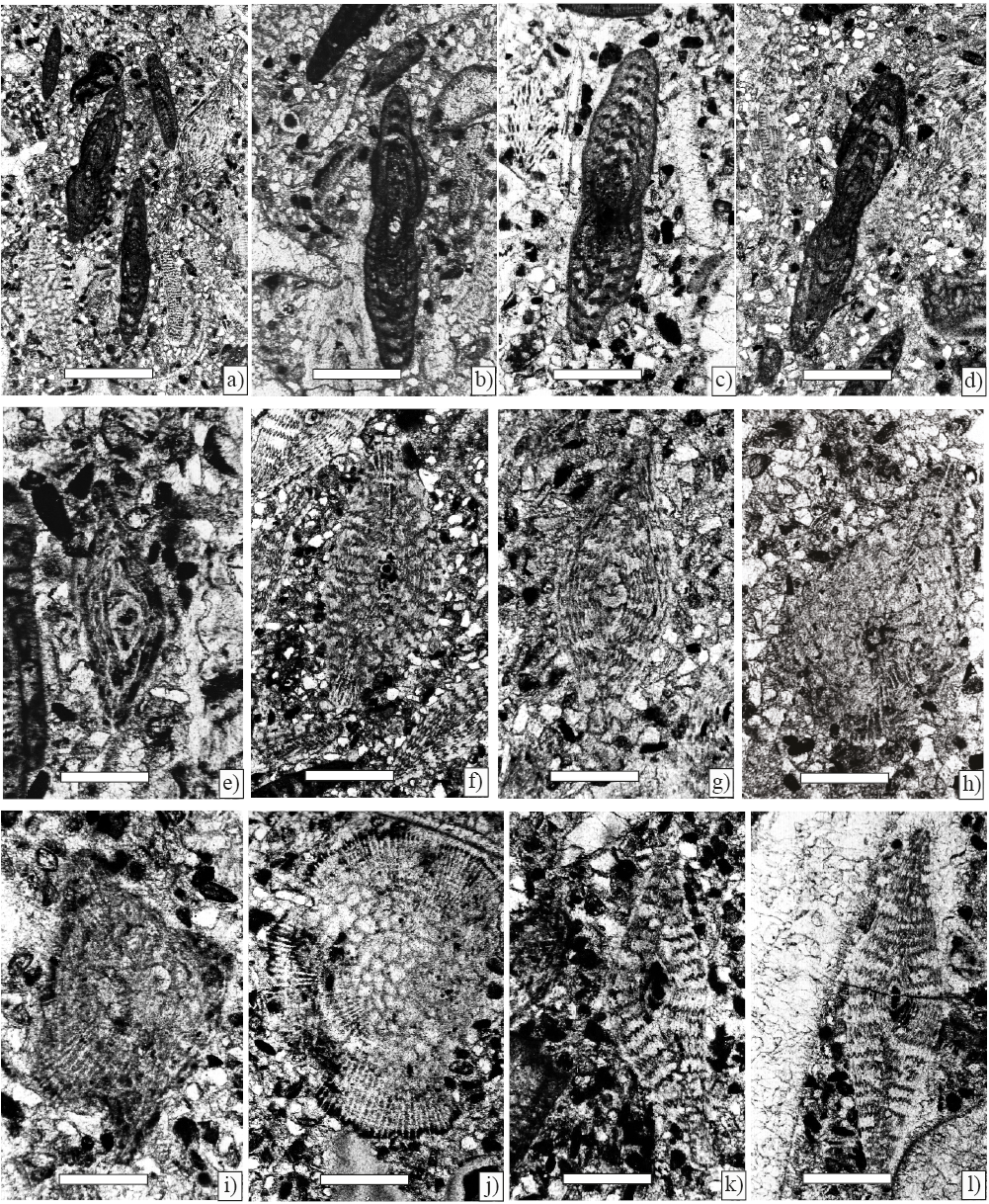

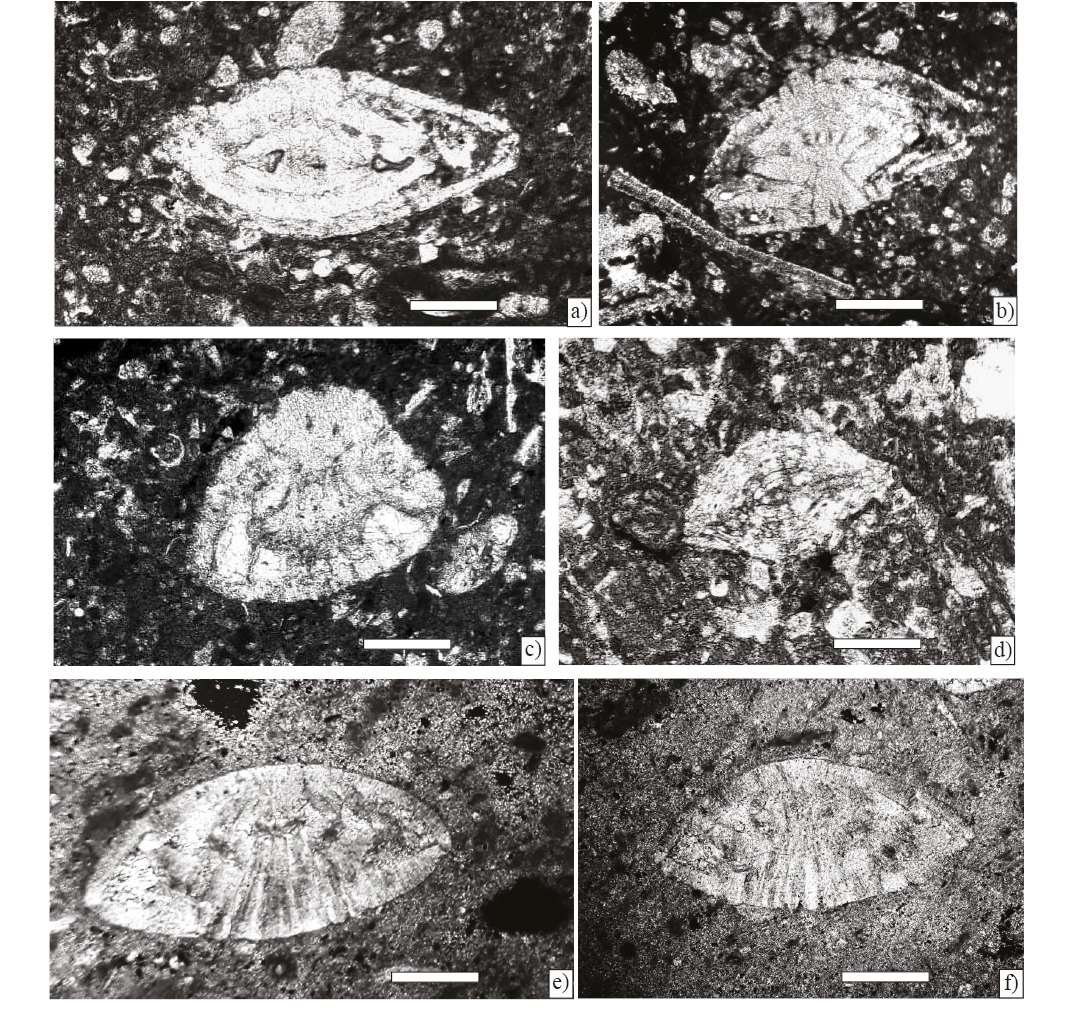

Definition. This zone is characterized by the assemblage of Pseudorbitoides rutteni Brönnimann, Ayalaina rutteni (Palmer) and Pseudorbitoides trechmanni Douvillé. Also contains Sulcoperculina dickersoni (Palmer), S. vermunti (Thiadens), S. globosa de Cizancourt (Figures 3a–3i).

Age. The stratigraphic distribution of pseudorbitoids is stated to be of Campanian–Maastrichtian; however, Pseudorbitoides rutteni Brönnimann is dated to early Maastrichtian age (Seiglie and Ayala-Castañares, 1963, p. 46). Renz (1955. p. 54) indicated that S. globosa de Cizancourt is a common species in the Venezuelan Maastrichtian. We assume that this zone could be of earliest Maastrichtian because underlies the Gansserina gansseri Interval Zone of early Maastrichtian age.

Remarks. This zone is proposed in this paper as local zone based on the benthic foraminiferal association.

Gansserina gansseri Interval Zone upper part (Ocozocoautla Formation, Sample P-754a–P-756)

Definition. Interval with the zonal marker Gansserina gansseri (Bolli). The lower boundary of the Gansserina gansseri Interval Zone has been defined by the First Occurrence (FO) of the nominal fossil. The upper limit was placed by the FO of Racemiguembelina fructicosa (Egger) according to Premoli Sivla and Sliter (1995), Premoli Silva and Verga (2004), Coccioni and Premoli Silva (2015).

Age. Latest Campanian–early Maastrichtian.

Remarks. According to Caron (1985) this zone is considered as of the late Maastrichtian. Subsequently, Premoli Silva and Sliter (1995) and Premoli Silva and Verga (2004) regarded it as latest Campanian–early Maastrichtian age.

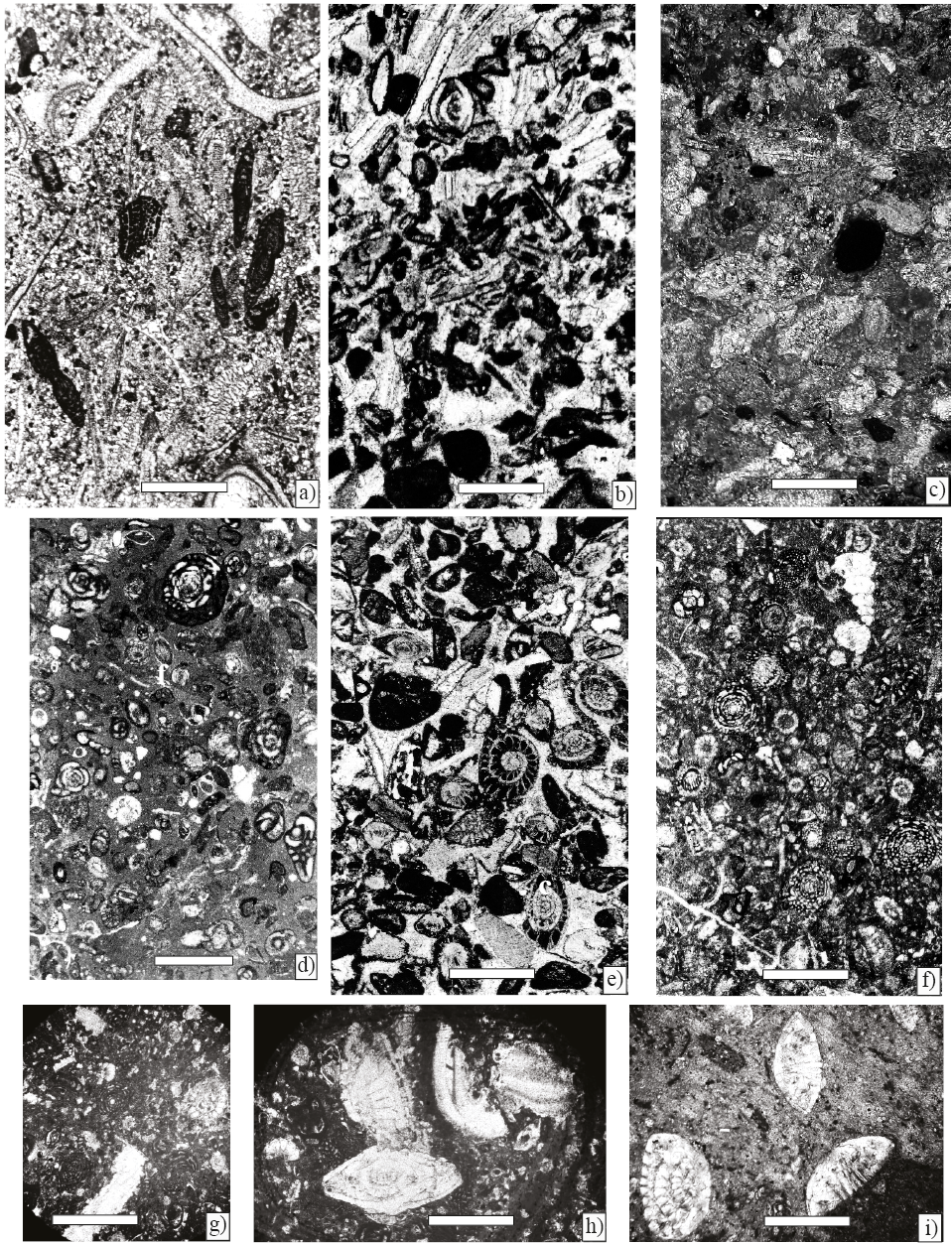

In this paper we identified Gansserina gansseri (Bolli) associated with Globotruncanita conica, (White), Rugoglobigerina hexacamerata Brönnimann, R. macrocephala Brönnimann, Pseudotextularia elegans (Rzehak), and Planoglobulina carseyae (Plummer) (Figure 4a–4h), these species appear in the upper part of the zone as has been cited by Premoli Silva and Sliter (1995); Premoli Silva and Verga (2004), Coccioni and Premoli Silva (2015), so an early Maastrichian age is assigned.

Additionally, Pons et al. (2016) reported ammonites from the Ocozocoautla Formation including Pachydiscus (P.) neubergicus (Hauer) that indicates an early Maastrichtian, the FO of this ammonite is considered to mark the base of the Maastrichtian (Odin and Lamaurelle, 2001, Ogg et al., 2012, p. 806).

Praechubbina breviclaustra Interval Zone (Angostura Formation, Sample P-744)

Definition. Interval from the FO of Praechubbina breviclaustra and the FO of Chubbina jamaicensis, it is characterized by a community mostly composed of the Praechubbina breviclaustra, Fourcade and Fleury, P. oxchucencis Vicedo et al. and Nezzazatinella picardi (Henson) (Figures 5a–5h).

Age. Early late Maastrichtian age.

Remarks. Praechubbina breviclaustra was described by Fourcade and Fleury (2001) from the Campanian Angostura Formation. Vicedo et al. (2013) described Praechubbina oxchucencis from the Angostura Formation assigning it to late Campanian–early Maastrichtian. In our material, the interval with both species overlays the Gansserina gansseri Zone and underlies the Chubbina jamaicensis Zone therefore we give an early late Maastrichtian age.

Chubbina jamaicensis Total Range Zone (Angostura Formation, Samples P-745 to P-749 and P-759 to P-762)

Definition. Total range of the nominal fossil.

Age. Late-latest Maastrichtian.

Chubbina jamaicensis was described for the first time by Robinson (1968) from the Cretaceous rocks of Jamaica, reporting that it is in the Guinea Corn Formation, associated with Titanosarcolites rudist fauna. Butterlin (1981) proposed a Chubbina Zone for the Campanian–Maastrichtian. Later, Mitchell (2005) commented that the first appearance of this genus is probably an important regional bioevent for dating the late Maastrichtian of the Greater Caribbean Region (the Antilles, Florida, Central America and northern South America). In addition, Chubbina macgillavryi Robinson is also considered to be a latest Maastrichtian marker (Vicedo et al., 2013, Figure 4). Other benthic larger foraminifera were also used for dating this interval, such as Orbitoides browni, which was described for the first time as Gallowayina browni by Ellis (1932) from Cuba, and later placed in the Orbitoides genus by Vaughan (1934), who found it associated with Omphalocyclus macroporus (Lamarck) on the Anaya River near Santa Clara, Cuba. Palmer (1934a) confirms Vaughan’s observation, inferring that the stratigraphic distribution of Orbitoides browni (Ellis) is restricted to the late Maastrichtian. Seiglie and Ayala-Castañares (1963) and Ayala-Castañares (1963) also proposed a late Maastrichtian age as established previously.

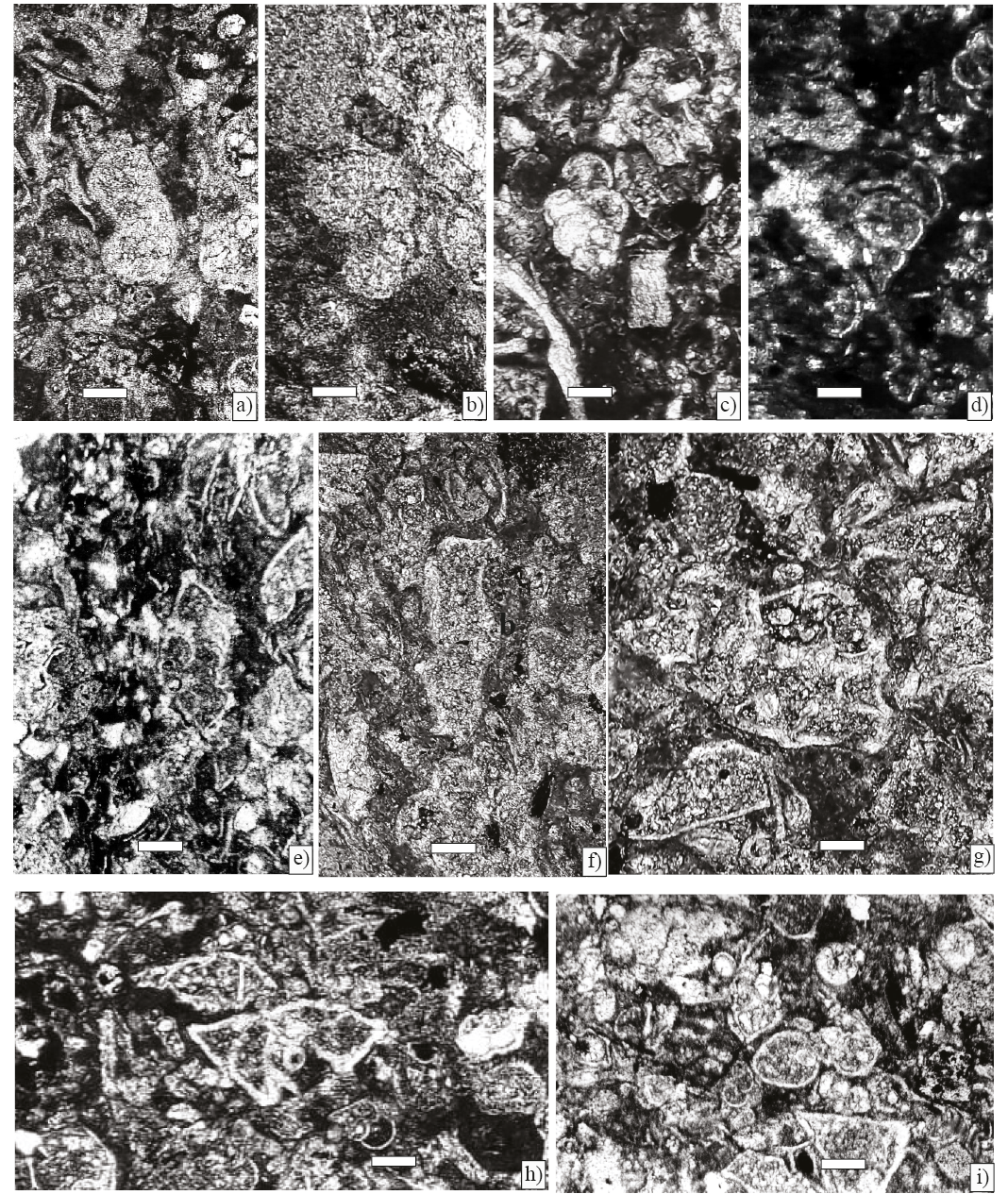

Remarks. This zone contains a rich association of larger benthic foraminifera and algae composed by Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, C. macgillavryi Robinson, Orbitoides browni (Ellis), Smoutina cruysi Drooger, Valvulina cf. V. triangularis d'Orbigny, Cuneolina ketini Inan, Fleuryana adriática De Castro, Drobne and Gušić. In addition, the dasycladacean algae Acroporella chiapasis Deloffre, Fourcade and Michaud, Neogyroporella? servaisi Michaud (Figures 6–9).

Figure 3. Larger foraminifera from Ocozocoautla Formation, scale bar 250 µm. a) Ayalaina rutteni (Palmer) and Pseudorbitoides; axial sections (Sample P-740). b) Ayalaina rutteni (Palmer), axial section; c), d) subaxial section (Sample P-740). e), f), g), h), and i) Pseudorbitoides rutteni Brönnimann; e) axial section of juvenile specimen; f), g) axial section; h) subequatorial section; i) tangential section (Sample P-740). j), k), and l) Pseudorbitoides trechmanni Douvillé; j) subequatorial section; k) l) subaxial section (Sample P-740).

Figure 4. Planktic foraminifers from Ocozocoautla Formation. Scale bar 50 µm. a) Gansserina gansseri (Bolli) (Sample P-754). b) Rugogoglobigerina macrocephala Bronnimann, axial section (Sample P-754). c) Planoglobulina carseyae (Plummer), axial section (Sample P-754). d) Pseudotextularia elegans (Rzahak), (Sample P-754). e) Globotruncana arca (Cushman), axial section (Sample P-754). f) Globotruncana linneiana (d'Orbigny), axial section (Sample P-754). g) Globotruncanita conica (White), axial section (Sample P-754). h) Globotruncanita pettersi (Gandolfi), Axial section (Sample P-754). i) Globotruncanella sp. axial section (Sample P-756).

Figure 5. Larger foraminifera from Angostura a)–g) and benthic foraminifera, planktic and pithonellid from Ocozocoautla Formations j)–h); scale bar 200 µm. a) b) and c) Praechubbina oxchucencis Vicedo et al. axial sections (Sample P-744). e) f) and g) Praechubbina breviclaustra Fourcade and Fleury, equatorial sections (Sample P-744). h) Nezzazatinella picardi (Henson). (Sample P-744). i) Vaughanina cubensis Palmer (Sample P-743). j) Heterohelix sp. (Sample P-741) 100 µm. k) Muricohedbergella holmdelensis (Olsson) (Sample P-741), scale bar 100 µm, Ocozocoautla Formation. h) Pithonella sphaerica (Kauffmann) (Sample P-741), scale bar 100 µm, Ocozocoautla Formation.

Paleoecology

The tropical and subtropical distribution of Recent larger foraminifera is controlled by environmental parameters such as light penetration until 150 m in clear waters; nutrient availability, turbidity, water depth, water temperature, and salinity (Hallock, 1984, 1988; Hallock and Glenn, 1986; Leutenegger, 1984; Hohenegger, 2000, 2004).

The extant species host photosynthetic algae as symbionts. This form of symbiosis is only effective in warm, oligotrophic environment within the photic zone. In modern seas symbiont-bearing foraminifera are restricted to areas with a minimum sea surface temperature of 16 °C in the coldest month (Langer and Hottinger, 2000). It could be inferred that the larger foraminifera in the Mesozoic had a similar distribution (Hohenegger, 2004, BouDhager-Fadel, 2008).

In addition, the ecology of larger fossil foraminifera with recent forms can be interpreted from the test architecture so Chubbina could be compared with the recent relatives for example with algal symbiont-bearing alveolinids, that inhabited shallow-water marine conditions in a warm climate (Hohenegger, 2000, 2004; Renema, 2002).

On the other hand, Langer (1993) suggests that Chubbina is comparable to the modern peneroplid morphotypes that probably lived as seagrass dwellers. Den Hartog (1970) claimed that Angiosperm seagrasses have been in existence since the Cretaceous, thus the first description of fossil sea grasses was from the early Campanian of the Netherlands by Debey (1848, 1851). Voigt and Domke (1955) reported Thalassocharis bosquetii Debey ex Miquel from the Late Maastrichtian of the Netherlands (in Van der Ham et al., 2007). Eva (1980) suggests that forms such as Chubbina and Ayalaina were adapted to a seagrass habitat.

Orbitoides with their biconvex morphology, may have either been living in seagrass areas or in slightly deeper water (Hottinger, 1997; Renema and Hart, 2012).

Pseudorbitoides, Vaughanina and Sulcoperculina inhabited warm shallow-water from moderate to high energy environment as suggest Goldbeck and Langer (2009).

Fleuryana adriatica and Cuneolina ketini dwelled in a protected environment (lagoon) as indicated by Inan et al. (2005, p. 372).

Microfacies and Paleoenvironment

Microfacies from the Ocozocoautla Formation

1- Foraminiferal–lithoclastic grainstone with Pseudorbitoides rutteni Brönnimann, Sulcoperculina dickersoni (Palmer), S. vermunti (Thiadens), and Ayalaina rutteni (Palmer), the matrix consists of angular fine sand sized quartz grains (Samples P-740 and P-743), (Figures 10 a, 10b).

Both the lithology and the faunal content suggest a warm shallow-water platform deposit with abundant siliciclastic input. Pseudorbitoides also inhabited a high-energy environment in turbulent waters with an increase of siliciclastic deposit, as has been stated by Seiglie and Ayala-Castañares (1963).

2- Wackestone with planktic foraminifera: Gansserina, Contusotruncana, Globotruncana, Globotruncanita. (Sample P-754) (Figure 10c).

An open hemipelagic marine influence with moderate to high energy can be inferred from the presence of planktic forms, it could be equivalent to SMF 3 of Flügel (2010).

Microfacies from the Angostura Formation

The following microfacies are referred to the SMF 18 characterized by abundant benthic foraminifera and algae (Flügel, 2010, p. 721).

3- Foraminiferal wackestone with Praechubbina, and Nezazzatinella (Sample P-744) (Figure 10d).

The fine grained of the matrix and the presence of Praechubbina which as other alveolinids flourished in shallow-water low energy lagoon environment.

4- Lithoclastic grainstone with Orbitoides, Sucoperculina, Vaughanina and gastropods (Sample P-750) (Figure 10e).

Orbitoides commonly occurs together with specimens of the genus Sulcoperculina. It is inferred that the genus Orbitoides inhabited a deeper environment, as indicated by Hohenegger (1999), and ranged into the upper photic zone at depths of about 40–80 m (Hottinger, 1997). In addition, the Orbitoides morphology, showing a thick lenticular test and terrigenous presence, suggests a high-energy open marine environment as proposed by Caus (1988) and Caus et al. (2002).

5- Foraminiferal–algal packstone–wackestone with alveolinids such as Chubbina, in addition to Smoutina, Valvulina, Nezzazatinella, Fleuryana, Cuneolina and algae Acroporella and Neogyroporella? (Samples P-746–P-749) (Figure 10f).

This foraminiferal association thrived in a soft substrate characterized by wackestone indicating a shallow protected lagoon environment with low hydrodynamic energy, within the euphotic zone indicated by the presence of algae (Deloffre et al., 1995; Michaud 1988).

Chubbina has previously been regarded as a dweller of this environment (Hamaoui and Fourcade, 1973; Robinson, 1968; Eva, 1980).

Fleuryana adriatica De Castro, Drobne and Gušić flourishes in a foraminiferan-dasycladacean soft substrate wackestone–packstone type into a shallow protected platform with low water energy (lagoon) as indicated by Schlagintweit and Rashidi (2016, p. 65).

Cuneolina ketini Inan inhabited lagoon environments associated with other species as Fleuryana adriatica De Castro, Drobne and Gušić in Slovenia (Inan et al., 2005, p. 372).

6- Wackestone–packstone with Sucoperculina, Vaughanina, Nezzazatinella (Sample P-752) (Figure 10g).

Sulcoperculina shows a wide range of adaptation, since it can live in a shallow open marine environment with highwater energy and the presence of siliciclastics (Golbeck and Langer, 2009).

Vaughanina is frequently associated with Sulcoperculina in a high-energy environment with abundant detritical particles. Seiglie and Ayala-Castañares (1963) thus conclude that the genera of the family Pseudorbitoididae lived in an environment with high water energy.

7- Foraminiferal wackestone with an association mostly composed by Smoutina, as well as Valvulina and Sulcoperculina (P-758) (Figures 10h and 10i).

The textured limestone suggests a lower energy lagoon environment with a reduced foraminiferal diversity.

Figure 6. Larger foraminifera from Angostura Formation, scale bar 250 µm. a) Chubbina macgillavryi Robinson, Equatorial sections(Sample P-747). b) Chubbina macgillavryi Robinson, equatorial sections(Sample P-746). c) Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, equatorial sections (Sample P-747). d) Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, equatorial sections (Sample P-746). e) Chubbina macgillavryi Robinson, equatorial sections (Sample P-745). f) Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, equatorial sections (Sample P-760). g), and h) Acroporella chiapasis Deloffre, Fourcade y Michaud (Sample P-760). i) Hemicyclammina sp. (Sample P-746). j) Valvulina cf. V. triangularis d' Orbigny (Sample P 7).

Figure 7. Benthic foraminifera and algae from Angostura Formation, scale bar 250 µm. a) and b) Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, axial sections of a microspheric form (Sample P-749). c) Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, equatorial sections of megalospheric form and Smoutina cruysi Drooger (Sample P-749). d), and e) Neogyroporella? servaisi Michaud, longitudinal and axial sections (Sample P-749). f) Fleuryana adriatica De Castro, Drobne and Gušić, equatorial section (Sample P-749). g) Cuneolina ketini Inan (Sample P-749).

Figure 8. Larger foraminifera from Angostura Formation, scale bar 200 µm. a) Sulcoperculina globosa de Cizancourt, axial section (Sample P-752). b) Smoutina cruysi Drooger, axial section (Sample P-749). c) Orbitoides browni (Ellis), axial section; d), e) Subaxial sections; f), g) Tangential sections; h) Axial section of the embryonic apparatus (Sample P-750).

Figure 9. Larger foraminifera from Angostura Formation, scale bar 200 µm. a) Sulcoperculina dickersoni (Palmer), axial section (Sample P-752 ). b) Sulcoperculina globosa de Cizancourt, axial section (Sample P-752 ). c) Sulcoperculina vermunti (Thiadens), equatorial section (Sample P-752 ). d) Vaughanina cubensis Palmer, subaxial (Sample P-752 ). e) Smoutina cruysi Drooger, axial section (Sample P-758).

Figure 10. Microfacies, scale bar 100 µm. a) Foraminiferal–lithoclastic grainstone with Ayalaina, Peudorbitoides (Sample P-740). b) Foraminiferal–lithoclasticgrainstone with Sulcoperculina (Sample P-743). c) Planktic foraminiferal wackestone (Sample P-754). d) Foraminiferal wackestone with Praechubbina, Nezazzatinella (Sample P-744). e) Foraminiferal grainstone with Orbitoides, Sucoperculina, Vaughanina and gastropods (Sample P-750). f) Foraminiferal–algal wackestone with Chubbina, Smoutina, Valvulina, Nezzazatinella, Fleuryana, Cuneolina, algae Acroporella and gastropods (Samples P-747). g) Wackestone–packstone with Sucoperculina, Vaughanina, Nezzazatinella (Sample P-752). h), and i) Foraminiferal wackestone with an association mostly composed by Smoutina cruysi Drooger, as well as Sulcoperculina and Valvulina (P-758).

Paleobiogeography

The planktic foraminiferal association consists of diversified groups such as keeled, trochospiral, planispiral, biserial, and multichambered forms, corresponding to the Tethysian Province (Premoli Silva and Sliter, 1999).

The larger foraminifera identified in the area as Ayalaina rutteni (Palmer), Sulcoperculina dickersoni (Palmer), S. vermunti (Thiadens), S. obesa de Cizancourt, Pseudorbitoides rutteni Brönnimann, P. trechmanni Douvillé, Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, C. macgillavryi Robinson, and Smoutina cruysi Drooger, Orbitoides browni (Ellis) are fossils which are well known as endemic forms of the Caribbean region and adjacent areas from the Bahamas (Hottinger, 1972); Mexico (Butterlin, 1981; Michaud, 1987; Rosales-Domínguez et al., 1997; Omaña, 2006; Omaña and Alencaster, 2019); Guatemala (Scott, 1995; Fourcade et al., 1999); Belize (Schafhauser et al., 2003); Cuba (Ellis, 1932; Palmer, 1934; 1934a; Vaughan, 1934; Voorwijk, 1937; Seiglie and Ayala-Castañares, 1963); Jamaica (Cole and Applin, I970; Krijnen, 1970; Mitchell, 2005); Haiti (Butterlin, 1956); Costa Rica (Jaccard et al., 2001; Baumgartner-Mora and Percy, 2002); Venezuela (de Cizancourt, 1949; Renz, 1955); Colombia (Caudri, 1948, p. 447). Additionally, these genera have been reported on Pacific islands (Beckmann, 1976; Premoli Silva and Brusa, 1981; Premoli Silva et al., 1995).

In addition, Tethysian benthic foraminifera are also registered in the Angostura Formation, such as Cuneolina ketini Inan, Fleuryana adriática De Castro, Drobne and Gušić, and have also been recorded from Italy and Slovenia by Caffau et al. (1998), Tewari et al. (2007), and Moro et al. (2018); in SW Slovenia (Ogorolec et al., 2007); Turkey (Inan and Inan, 2009; Solak et al., 2017); in Algeria (Tawadros, 2012, p. 448); in Iran, by Schlagintweit and Rashid (2016). In the New World Fleuryana adriatica has been recorded in Guatemala by Fourcade et al., 1999,) (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Maastrichtian paleogeographic map showing the distribution of larger foraminifera in shallow-water environment with assumed locations.

DISCUSSION

The term “Gravas Ocozocoautla” has a long history since it was first used by Sapper (1894), and subsequently mentioned by Page and Pike (1921) in an unpublished report; later Gutiérrez Gil (1956) and Chubb (1959) also published about this unit. The dating of the unit is controversial, since Brönnimann (in Chubb, 1959) assigned a probable Campanian age to the microfauna of the basal Piedra Parada from the Ocozocoautla Formation. After, Sánchez-Montes de Oca (1973, p. 14) indicated that the Ocozocoautla Formation has a reduced geographical distribution limited NW of the central Chiapas Depression and revealed that this formation interfingered with the Angostura Formation towards the southeast of the town of Ocozocoautla. This author points to that in the Turipache section, the Ocozocoautla Formation contains inoceramids and ammonites. Based on a study of the ammonites, a Campanian and part of Maastrichtian age was determined in the section before mentioned.

The term Angostura Formation was proposed by Sánchez-Montes de Oca (1973, p. 16) and the Coyol section located 50 km SE of Tuxtla Gutierrez as type locality. The unit spreads towards the NE of Chiapas State, and two foraminiferal biostratigraphic zones were recognized: one of orbitoids and other one of alveolinids of Campanian–Maastrichtian age.

Later, Michaud (1987, p. 171) analyzed the planktic foraminifera from washed samples from the interval with inoceramids of the Ocozocoautla Formation and dated it as late Campanian–Maastrichtian. He characterized the Angostura Formation by the presence of Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson and indicated that it could be of Campanian–Maastrichtian, although in the Ocozocoautla and El Naranjo sections Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson was found over the planktic levels, so it was assigned to the Maastrichtian age.

Mandujano Velázquez and Vásquez Meneses (1996) and Rosales-Domínguez et al. (1997) agreed with the proposal of Sánchez-Montes de Oca (1973) with respect to the stratigraphical relationships and age of the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations.

Omaña (2006) studied the planktic foraminifera obtained from chemical treatment of samples of the inoceramid beds of the Ocozocoatla Formation, dating it as early Maastrichtian (upper part of the Gansserina gansseri Interval Zone), assigning a precise age to these strata. Omaña and Alencaster (2019) reported late-latest Maastrichtian larger foraminifera at locality type of the Angostura Formation from samples collected by Quezada-Muñetón (Petróleos Mexicanos retired geologist).

Pons et al. (2016) considered that the Angostura Formation overlies the Ocozocoautla unit, based on paleontological studies (rudists and ammonites) in the studied region and the fact that they are not laterally equivalent as was documented in previous works (Sánchez-Montes de Oca, 1969; Mandujano Velázquez and Vásquez Meneses,1996 and Rosales-Domínguez et al., 1997).

This paper is a significant contribution because we defined the foraminiferal biostratigraphy during the deposit of the Ocozocoautla and Angostura formations, presenting an accurate dating of the two units. We assigned the former an earliest-early Maastrichtian age and the second a late-latest Maastrichtian age, in contrast to the view previously expressed in the literature, which has often indicated undifferentiated Campanian–Maastrichtian.

CONCLUSIONS

The Ocozocoautla Formation contains a community composed of benthic larger foraminifera, Pseudorbitoides rutteni Brönnimann, P. trechmanni Douvillé, Ayalaina rutteni (Palmer) also Sulcoperculina dickersoni (Palmer), S. vermunti (Thiadens), S. globosa de Cizancourt, Nezzazatinella picardi (Henson) and stratigraphically significant planktic foraminifera such as Gansserina gansseri (Bolli), Contusotruncana walfishensis (Todd), Globotruncanita conica (White), G. pettersi (Gandolfi), Rugoglobigerina macrocephala Brönnimann, R. hexacamerata Brönnimann, Pseudotextularia elegans (Rzehak), Planoglobulina carseyae (Plummer). Two zones were recorded: the Pseudorbitoides rutteni–Ayalaina rutteni Assemblage Zone of earliest Maastrichtian and the upper part of the Gansserina gansseri Interval Zone of early Maastrichtian age.

The Angostura Formation comprises an assemblage composed of dasycladacean algae such as Acroporella chiapasis, Deloffre, Fourcade and Michaud, Neogyroporella? servaisi. Michaud, as well as larger foraminifera Chubbina jamaicensis Robinson, C. macgillavryi Robinson, Orbitoides browni, (Ellis), Fleuryana adriática De Castro, Drobne and Gušić, Cuneolina ketini, Inan, and Valvulina cf. V. triangularis d'Orbigny. Two zones were identified: Praechubbina breviclaustra Interval Zone of early late Maastrichtian and Chubina jamaicensis Total Range Zone of late-latest Maastrichtian.

A variety of microfacies changing from grainstone to wackestone-packstone to wackestone, with different foraminiferal associations, indicate the development of various environments from to an open marine setting with planktic foraminifera with high water energy in the Ocozocoautla Formation to a restricted carbonate shallow-water environmentfrom the Angostura Formation.

The foraminiferal association in these units contains mostly endemic genera such as Pseudorbitoides, Ayalaina, Praechubbina, Chubbina, Sulcoperculina, Vaughanina, which are restricted to the Upper Cretaceous deposits from the Caribbean Province including Mexico, Guatemala, Cuba, Florida, Jamaica, Puerto Rico and Venezuela and some localities in the Pacific region, as well as Orbitoides browni (Ellis), which is regarded as an American species.

Some Tethysian species have been identified in the Angostura Formation, which previously have been recorded from Italy, Slovenia Tukey, Iran and Algeria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the Instituto de Geología of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for supporting this study. We are grateful to Drs. Carmen Rosales Domínguez, Raquel Robles Salcedo and specially to anonymous reviewer for the useful comments and suggestions that significantly improved the manuscript. We are deeply thankful to Dr. Angel F. Nieto Samaniego Editor in Chief (Centro de Geociencias UNAM, Juriquilla Mexico), for his careful editorial handling of our article. We would like to Ing. J Jesús Silva Corona Technical Editor (Centro de Geociencias, UNAM, Juriquilla, Mexico) by the final review of the manuscript.

We thank Diego and Joaquín Aparicio for preparing numerous thin sections and Lic. Ofelia Barrientos who provides bibliographic information.

REFERENCES

Alencáster, G. 1971, Rudistas del Cretácico Superior de Chiapas. Parte 1: Paleontología Mexicana, 34, 1-91.

Alencáster, G., Pons, J.M., 1992, New observations on the Upper Cretaceous rudists of Chiapas; comparison between American and European faunas and taxonomic implications: Geologica Romana, 28, 327-340.

Alencáster, G., Omaña, L., 2006, Maastrichtian inoceramid bivalves from Central Chiapas, Southeastern Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 80(5), 946-957.

Ayala-Castañares, A., 1963, Foraminíferos grandes del Cretácico Superior de la Región Central de Chiapas, México, Parte 1. El género Orbitoides d’Orbigny 1847: Paleontología Mexicana, 13, 57-63.

Baumgartner-Mora C., Percy, D., 2002, Campanian–Maastrichtian limestone with larger foraminífera from Peña Bruja Rock (Santa Elena Peninsula): Revista Geológica de América Central, 26, 85-89.

Beckmann, J.P., 1976, Shallow-water foraminifers and associated microfossils from sites 315 and 318 DSDP Leg 33: Deep Sea Drilling Project, vol. XXXIII, 467-489.

Bolaños, L., Buitrón, B., 1984, Contribución al conocimiento de los Inocerámidos de México, in Perrilliat, M.C. (ed.), Memoria del III Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología: Oaxtepec, Morelos, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología, 406-414.

BouDhager-Fadel, M., 2008, Evolution and geological significance of larger benthic foraminífera, in Wignall, P.B. (ed.), Developments in Palaeontology and Stratigraphy 21: Elsevier Amsterdam, 515 pp.

Buitrón, B., Rosales-Domínguez, C., Espinosa, L., 1995, Some Mollusks (Tellinidae, Turrillellidae, Cerithidae, Aporrhaidae and Naticidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Ocuilapa, Chiapas and its relationship to the Northern American and Caribbean Provinces: Revista de la Sociedad Mexicana de Paleontología, 8(1), 1-22.

Butterlin, J.,1956, Une microfaune nouvelle du Crétacé Supérieur de la République d'Haiti: Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 6(6), 163-167.

Butterlin, J., 1981, Claves para la determinación de macroforaminíferos de México y del Caribe, del Cretácico Superior al Mioceno medio: Instituto Mexicano del Petróleo, 3-97.

Caffau, M., Plenicar M., Pugliese, N., Drobne, K., 1998, Late Maastrichtian Rudists and microfossils in the Karst Region (NE Italy and Slovenia): Geobios, 22, 37-46.

Carbot-Chanona, G., Rivera-Sylva, E.H, 2011, Presence of a maniraptoriform dinosaur in the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Chiapas, southern Mexico: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana,63 (3), 393-398 http://dx.doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2011v63n3a2

Carbot-Chanona, G., Than-Marchese, B.A., 2013, Presencia de Enchodus (Osteichthyes: Aulopiformes: Enchodontidae) en el Maastrichtiano (Cretácico Tardío) de Chiapas, México: Paleontología Mexicana, 63, 8-16.

Caron, M., 1985, Cretaceous Planktonic Foraminifera, in Bolli, H.M., Saunders, J.B., Perch-Nielsen, K. (eds.), Plankton Stratigraphy: Cambridge, London, Cambridge University Press, 17-86.

Caudri, M.B., 1948, Note on the stratigraphic distribution of Lepidorbitoides: Journal of Paleontology, 22(4), 473-481.

Caus, E., 1988, Upper Cretaceous larger foraminifera: paleoecological distribution: Revue de Paléobiologie, Special Volume 2, 417-419.

Caus, E., Tambareau, Y., Colin, J.P., Aguilar, M., Bernaus, J.M., Gómez-Garrido, A., Brusset, S., 2002, Upper Cretaceous microfauna of the Cárdenas Formation, San Luis Potosí, NE Mexico. Biostratigraphical, palaeoecological, and palaeogeographical significance: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 19(1), 137-144.

Chubb, L.J., 1959, Upper Cretaceous of Central Chiapas, Mexico: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 43(4), 725-756.

Cizancourt, M. de, 1949, Matériaux pour la paléontologie et la stratigraphie de régions Caraïbes: Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, ser. 5, 18, fasc 8-9, 663-674.

Coccioni, R., Premoli Silva, I., 2015, Revised Upper Albian-Maastrichtian planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy and magneto-stratigraphy of the classical Tethyan Gubbio section (Italy): Newsletters on Stratigraphy, 48/1, 47-90, DOI: 10.1127/nos/2015/0055

Cole, W.S., Applin, E.R., 1970, Analysis of some American Upper Cretaceous larger foraminifera: Bulletin of American Paleontology, 58, 39-80.

Debey, M.H., 1848, Uebersicht der urweltlichen Pflanzen des Kreidegebirges überhaupt und der Aachener Kreideschichten insbesondere: Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereines der Preussischen Rheinlande, 5, 113-125.

Debey, M.H., 1851, Beitrag zur fossilen Flora der holländischen Kreide (Vaels bei Aachen, Kunraed, Maestricht): Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereines der Preussischen Rheinlande, 8, 568-569.

Deloffre, R., Fourcade, E., Michaud, F., 1985, Acroporella chiapasis nov. sp., algue dasycladacea du Maastritchtien du Chiapas (SE Mexique): Bulletin Centre Research Exploration Production, Elf Aquitaine, 9(1), 115-125.

Den Hartog, C., 1970, The Seagrasses of the World: Amsterdam, North Holland Publishing Co., 275 pp.

Ellis, B.F.,1932, Gallowayina browni, a new genus and species of orbitoid from Cuba, with notes on the American occurrence of Omphalocyclus macropora: American Museum Novitates, 568, 1-8.

Eva, A.N., 1980, Pre-Miocene seagrass communities in the Caribbean: Palaeontology, 23, 231-236.

Filkorn, H., Avendaño-Gil, J., Coutiño-José, M.A., Vega-Vera, F.J., 2005, Corals from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Ocozocoautla Formation, Chiapas, México: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 22(1), 115-128.

Flügel, E., 2010, Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks. Analysis, Interpretation and Applications, 2nd Edition, Berlin, Springer, 976 pp.

Fourcade, E., Fleury, J.J., 2001, Origine, évolution et systématique de Praechubbina n. gen., foraminifères alveolinacea du Crétacé Supérieur du Guatemala et du Mexique: Revue de Micropaleontologie, 44 (2), 125-157.

Fourcade, E., Michaud, F., 1987, L’ouverture de l’Atlantique et son influence sur les peuplements des grands foraminifères des plates-formes péri-océaniques au Mésozoïque: Geodinamica Acta, 1, 247-262.

Fourcade, E., Piccioni, L., Escribá, J., Rosselo, E., 1999, Cretaceous stratigraphy and paleoenvironments of the Southern Petén Basin, Guatemala: Cretaceous Research, 20, 793-821.

Goldbeck, E.J., Langer, M.R., 2009, Biogeographic Provinces and Patterns of diversity in selected Upper Cretaceous (Santonian-Maastrichtian) Larger Foraminifera Geologic Problem Solving with Microfossils: A Volume in Honor of Garry D. Jones, SEPM, Society for Sedimentary Geology, SEPM Special Publication No. 93, 187-232.

Gutiérrez Gil, R., 1956, Geología del Mesozoico y estratigrafía pérmica del Estado de Chiapas, in XX Congreso Geológico Internacional Guidebook, Excursión C–15: México, D.F., Mexico, Instituto Geológico de México, 82 pp.

Hallock, P., 1984, Distribution of selected species of living algal symbiont-bearing foraminifera on two pacific coral reefs: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 14, 250-261.

Hallock, P., 1988, Diversification in algal symbiont-bearing Foraminifera: A response to oligotrophy?: Revue de Paléobiologie, vol. spécial, 2, Benthos’86, 789-797.

Hallock, P., Glenn, E.C., 1986, Larger Foraminifera: A tool for paleoenvironmental analysis of Cenozoic carbonate depositional facies: Palaios, 1, 55-64.

Hamaoui, M., Fourcade, E., 1973, Révision des Rhapydionininae (Alveolinidae, Foraminifera): Bulletin du Centre de Recherches de Pau Société Nationale des Pétroles d’Aquitaine-SNPA, 7, 361-435.

Hohenegger, J., 1999, Larger foraminifera-microscopical greenhouses indicating shallow-water tropical and subtropical environments in the present and past: Kagoshima University, Research Center for the Pacific Islands, Occasional Papers, 32, 19-45.

Hohenegger, J., 2000, Coenoclines of larger foraminifera: Micropaleontology, 46, Supl. 1, 127-151.

Hohenegger, J., 2004, Depth coenoclines and environmental considerations of western Pacific larger foraminifera: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 34, 9-33.

Hottinger, L., 1972, Campanian larger foraminifera from site 98, Leg 11 of Deep-Sea Drilling Project (Northwest Providence Channel, Bahama Islands), 595-605.

Hottinger, L., 1997, Shallow benthic foraminiferal assemblage as signals for depth of their depositation and their correlation: Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France,168(4), 491-505.

Hyžný, M., Vega, F., Coutiño, M., 2013, Ghost shrimps (Decapoda: Axiidea: Callianassidae) of the Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) Ocozocoautla Formation, Chiapas (Mexico): Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 65(2), 255-264.

Inan, N., Inan, S., 2009, Endemic foraminifera of the Late Maastrichtian from the northern branch of the Neotethys, NE Turkey: Micropaleontology, 55 (5),514-522.

Inan N., Tasli K., Inan, S., 2005, Laffitteina from the Maastrichtian-Paleocene shallow marine carbonate successions of the Eastern Pontides (NE Turkey): biozonation and microfacies: Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 25, 367-378.

Jaccard, S., Münster, M., Baumgartner, P.O., Baumgartner-Mora, C., Denyer, P., 2001, Barra Honda (upper Paleocene-lower Eocene) and el Viejo (Campanian-Maastrichtian) carbonate platforms in the Tempisque Area (Guanacaste, Costa Rica): Revista Geológica de América Central, 24, 9-28.

Kaufmann, F.J., 1865, Polythalamien des Seewerkalkes, in Heer, O. (ed.), Die Urwelt der Schweiz: Zürich, Friedrich Schulthees, 194-199.

Krijnen, J.P., 1970, Analysis of pseudorbitoids from Glenbrook, Jamaica, and discussion of a study by Cole and Applin: Scripta Geologica, 4 (1971), 1-15.

Langer, M.R., 1993. Epiphytic foraminifera: Marine Micropaleontology, 20, 235-265.

Langer, M., Hottinger, L., 2000, Biogeography of selected “larger foraminifera”: Micropaleontology 46 (Supplement 1), 105-127.

Leutenegger, S., 1984, Symbiosis in benthic foraminifera: specificity and host adaptations: Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 14, 16-35.

Löser, H., 2012, Corals from the Maastrichtian Ocozocoautla Formation (Chiapas, Mexico) a- closer look: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 9(3), 534-550.

Mandujano Velásquez, J., Vázquez Meneses, M.E., 1996, Reseña bibliográfica y análisis estratigráfico de la Sierra de Chiapas: Boletín de la Asociación Mexicana de Geólogos Petroleros, 45(1), 20-45.

Michaud, F., 1984, Algunos fósiles de la Formación Ocozocuautla; Cretácico Superior de Chiapas, México, in Perrilliat, C. (ed.), Memoria del III Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología: Oaxtepec, Mexico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología, 425-431.

Michaud, F., 1987, Stratigraphie et paléogéographie du Mesozoique du Chiapas (Sud Est du Mexique): Paris, France, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Mémoires des Sciences de la Terre, PhD Thesis, 17-298.

Michaud, F.,1988, Neogyroporella? servaisi nouvelle dasycladacee du Maastrichtien du Chiapas sud-est du Mexique: Cretaceous Research, 9, 369-378.

Michaud, F., Fourcade, E., 1989, Stratigraphie et paléogéographie du Jurassique et du Crétacé de Chiapas (Sud Est du Mexique): Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 3, 639-650.

Mitchell, S.F., 2005, Biostratigraphy of late Maastrichtian larger foraminifers in Jamaica and the importance of Chubbina as a late Maastrichtian index fossil: Journal of Micropalaeontology, 24, 123-130.

Moro, A., Velic, I., Mikuž, V., Horvat, A., 2018, Microfacies characteristics of carbonate cobble from Campanian of Slovenj Gradec (Slovenia): implications for determining the Fleuryana adriatica De Castro, Drobne and Gušic paleoniche and extending the biostratigraphic range in the Tethyan realm: The Mining-Geology-Petroleum Engineering Bulletin, 1-13, DOI: 10.1177/rgn.2018.4.1

Müllerried, F.K., 1931, Chiapasella, un paquiodonto extrañísimo de la América: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Anales del Instituto de Biología, 2(3), 243-284.

Müllerried, F.K., 1934, Sobre el hallazgo de pachiodontos gigantescos en el Cretácico de Chiapas: Anales del Instituto de Biología Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 5(11), 81-82.

Odin, G,S., Lamaurelle, M.A., 2001, The global Campanian- Maastrichtian stage boundary: Episodes, 24(4), 229-238.

Ogg, G., Hinnov, L.A., Huang, C., 2012, Cretaceous, in Gradstein, F.M., Ogg, J., Schmitz,M., Ogg, G. (eds.), The Geological Time Scale, Chapter 24: Amsterdam, Elsevier, 793-853, https://doi.org/10.1016/C2011-1-08249-8

Ogorelec, B., Dolenec, T., Drobne, K., 2007, Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary problem on shallow carbonate platform: Carbon and oxygen excursions, biota and microfacies at the K/T boundary sections Dolenja Vas and Sopada in SW Slovenia, Adria CP: Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 255, 64-76.

Omaña, L., 2006, Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) foraminiferal assemblage from the inoceramid beds, Ocozocoautla Formation, central Chiapas, SE Mexico: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 23(2), 125-132.

Omaña, L., Alencaster, G., 2019, Late-latest Maastrichtian foraminiferal assemblage from the Angostura Platform, Chiapas, SE Mexico: Biostratigraphic, paleoenvironmental and paleobiogeographic significance: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 91, 203-213.

Omaña, L., Pons, J.M., 2003, Ocurrence of Ayalaina ruttteni (Palmer) in the Maastrichtian platform deposits from two Mexican deposits localities, in Soto, L.D. (ed.), Agustín Ayala Castañares Universitario Impulsor de la Investigación Científica: México, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma, 273-282.

Page, J.H., Pike, R.W., 1921, Report of geological reconnaissance in Department of Tuxtla, Mezcalapa and Pichucalco: Geological Report 4 (unpublished).

Palmer, D.K., 1934, Some larger foraminífera from Cuba: Sociedad Cubana de Historia Natural Memoria, 8(4), 235-262.

Palmer, D.K., 1934a, The Upper Cretaceous Age of the Orbitoidal Genus Gallowayina Ellis: Journal of Paleontology, 8(1), 68-70.

Pons, J.M., Vicens, E., Martínez, R., García-Barrera, P., Nieto, I.E., Oviedo, A., Avendaño-Gil, M.J., 2016, The Campanian-Maastrichtian rudist bivalves succession in the Chiapas central depression, Mexico: Cretaceous Research, 60, 210-220.

Pons, J., Vincens, E., García-Barrera, P., 2019, Campanian and Maastrichtian hippuritid rudists (Hippuritida, Bivalvia) of the Chiapas Central Depression (southern Mexico) and implications for American multiple–fold hippuritid taxonomy: Journal of Paleontology, 93(2), 291-311.

Premoli Silva, I., Brusa, C., 1981, Shallow-water skeletal debris and larger foraminifers from the Deep-Sea Drilling Project Site 462, Nauru Basin, Western Equatorial Pacific: Deep Sea Drilling Project Volume LXI, 439-473.

Premoli Silva, I., Sliter, W.V, 1995, Cretaceous planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy and evolutionary trends from the Bottaccione section, Gubbio, Italy: Paleontographia Italica, 82, 1-89.

Premoli Silva, I., Sliter, W.V., 1999, Cretaceous paleoceanography: Evidence from planktonic evolution, in Barrera, E., Johnson, C.C. (eds.), Evolution of the Cretaceous Ocean-Climate System: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America, Special Paper 332, 301-328.

Premoli Silva, I., Verga, D., 2004, Practical Manual of Cretaceous Planktonic Foraminifera. International School on Planktonic Foraminifera, in Verga, D., Rettori, R. (eds.), 3o Course: Cretaceous: Perugia, Italy, Universities of Perugia and Milan, International School on Planktonic Foraminifera, Tipografia Pontefelcino, 283 pp.

Premoli Silva, I., Nicora, A., Arnaud Vanneau, A., 1995, Upper Cretaceous Larger Foraminifer Biostratigraphy from Wodejabato Guyot, Sites 873 through 8771, in Haggerty, J.A., Premoli Silva, L, Rack, F., McNutt, M.K. (eds.), Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program: Scientific Results, 144, 171-197.

Renema, W., 2002, Larger foraminifera as marine environmental indicators: Scripta Geologica, 124, 1-260.

Renema, W., Hart, M., 2012, Larger benthic foraminifera of the Type Maastrichtian, in Jagt, J.W.M., Donovan, S.K., Jagt-Yazykova, E.A. (eds.), Fossils of the Type Maastrichtian (Part 1): Scripta Geologica Special Issue, 8, 33-43.

Renz, H.H., 1955, Some Upper Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary foraminifera from Aragua and Guárico, Venezuela: Micropaleontology, 1, 52-71.

Robaszynski, F., Caron, M., 1995, Foraminifères planctoniques du Crétacé: commentaire de la zonation Europe-Méditerranée: Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 166(6), 681-692.

Robinson, E., 1968, Chubbina, a new Cretaceous alveolinid genus from Jamaica and Mexico: Palaeontology, 11, 526-534.

Rosales-Domínguez, M.C., Bermúdez-Santana, J., Aguilar-Piña, M., 1997, Mid and Upper Cretaceous foraminiferal assemblages from the Sierra de Chiapas, southern Mexico: Cretaceous Research, 18, 697-712.

Salvador, A., 1991, Origin and development of the Gulf of Mexico basin, in Salvador, A. (ed.), The Gulf of Mexico Basin: The Geology of North America, Austin, Texas, 389-444.

Sánchez-Montes de Oca, R., 1969, Estratigrafía y paleogeografía del Mesozoico de Chiapas: Mexico, Instituto Mexicano del Petróleo, Seminario sobre Exploración Petrolera, Mesa Redonda, Problemas de Exploración de la Zona Sur, 5(4), 31 pp.

Sánchez-Montes de Oca, R., 1973, Proyecto Mesozoico Arrecifal, Sierra de Chiapas, México: Mexico, Petróleos Mexicanos, Zona Sur, Informe Geológico, 581, 1-59 (unpublished).

Sapper, K., 1894, Informe sobre la geografía física y la geología de los Estados de Chiapas y Tabasco: Boletín de Agricultura, Minería e Industria, 3, 197-211.

Schafhauser, A., Stinnesbeck, W., Holland, B., Adatte T., Remane, J., 2003, Lower Cretaceous pelagic limestones in southern Belize: Proto-Caribbean deposits on the southeastern Maya Block, in Bartolini, C., Buffler R.T., Blickwede, J. (eds.). The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon habitats, basin formation, and plate tectonics: The American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir, 79, Tulsa Oklahoma, USA, 624-637.

Schlagintweit, F., Rashidi, K., 2016, Some new and poorly known benthic foraminifera from the late Maastrichtian shallow-water carbonates of the Zagros Zone, SW Iran: Acta Palaeontologica Romaniae, 12, 1, 53-70.

Scott, R.W., 1984, Mesozoic biota and depositional systems of the Gulf of Mexico–Caribbean region, in Westermann, G.E.G. (ed.), Jurassic–Cretaceous Biochronology and Paleogeography of North America: Geological Association of Canada, Special Paper 27, 49-64.

Scott, R.W., 1995, Cretaceous Rudists of Guatemala: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 12(2), 294-306.

Seiglie, G.A., Ayala-Castañares, A., 1963, Sistemática y bioestratigrafía de los Foraminíferos grandes del Cretácico Superior (Campaniano y Maastrichtiano) de Cuba: Paleontología Mexicana, 13, 1-56.

Solak, C., Taslı, K., Koç, H., 2017, Biostratigraphy and facies analysis of the Upper Cretaceous-Danian? platform carbonate succession in the Kuyucak area, western Central Taurides, S Turkey: Cretaceous Research, 79, 43-63.

Tawadros, E., 2012, Geology of North Africa: 15; Phanerozoic Geology of Algeria. Taylor and Francis Group, 446-449.

Tewari, V.C., Stenni, B., Pugliese, N., Drobne, K., Riccamboni, R., Dolenec, T., 2007, Peritidal sedimentary depositional facies and carbon isotope variation across K/T boundary carbonates from NW Adriatic platform: Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 255, 77-86.

Van der Ham, R.W.J.M., Konijnenburg van Citter J.H.A., Indeherberger, L., 2007, Sea-grass foliage from the Maastrichtian type area (Maastrichtian Danian) NE Belgium SE Netherlands: Review of Paleobotany and Palinology, 144(3-4), 301-321.

Vaughan, T.W.,1934, A Note on Orbitoides browni (Ellis): Journal of Paleontology, 8(1), 70-72.

Vega, F.J, Feldmann, R.M., García Barrera, P, Filkorn, H, Pimentel, F, Avendaño, J., 2001, Maastrichtian Crustacea (Brachyura: Decapoda) from the Ocozocoautla Formation in Chiapas, southeast Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 75, 319-329.

Vega, F., Charbonnier, S., Gómez Pérez, L.E., Coutiño, M.A., Carbot-Chanona, G., de Araújo Távora, V., Serrano Sánchez, M.L., Téodori, D., Hernández Monzón, O., 2018, Review and additions to the Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) Crustacea from Chiapas, Mexico: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 85, 325-344.

Vicedo, V., Caus, E., Frijia, G., 2013, Late Cretaceous alveolinaceans (larger foraminifera) of the Caribbean palaeobioprovince and their stratigraphic distribution: Journal Systematic Palaeontology, 11(1), 1-25.

Voigt, E., Domke, W., 1955, Thalassocharis bosqueti Debey ex Miquel, ein strukturell erhaltenes Seegras aus der holländische Kreide: Mitt. Geol. Staatsinst. Hambg. 24, 87-102.

Voorwijk, G.H., 1937, Foraminifera from the Upper Cretaceous of Habana, Cuba: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Amsterdam, Proceedings of the Section of Science, 40(2), 190-198.